“I used to give a lot of art away to people,” reflects Damien Hirst at one of his sprawling West London studios. “And they’d always sell it after a lot less time than I thought they would. You know, they wouldn’t sell it for leukaemia treatment for their children or mother or something; they’d sell it to buy handbags. And I’d be like, ‘Damn, I hate that!’”

Hirst is not on a quest to make a few bucks from a collectible nonfungible token (NFT). He’s not particularly interested in celebrating career highlights, or even attracting a younger, richer, snazzier audience.

He wants to know where the line between art and money is drawn — and if it can be drawn at all.

“And I suppose this whole project is like a test of that sort of area, right? I came to terms with it — it’s like, you know, when you walk downstairs in your house if you got a painting, and it’s not long before the spots represent dollar signs. I’ve been thinking about that for a long time.”

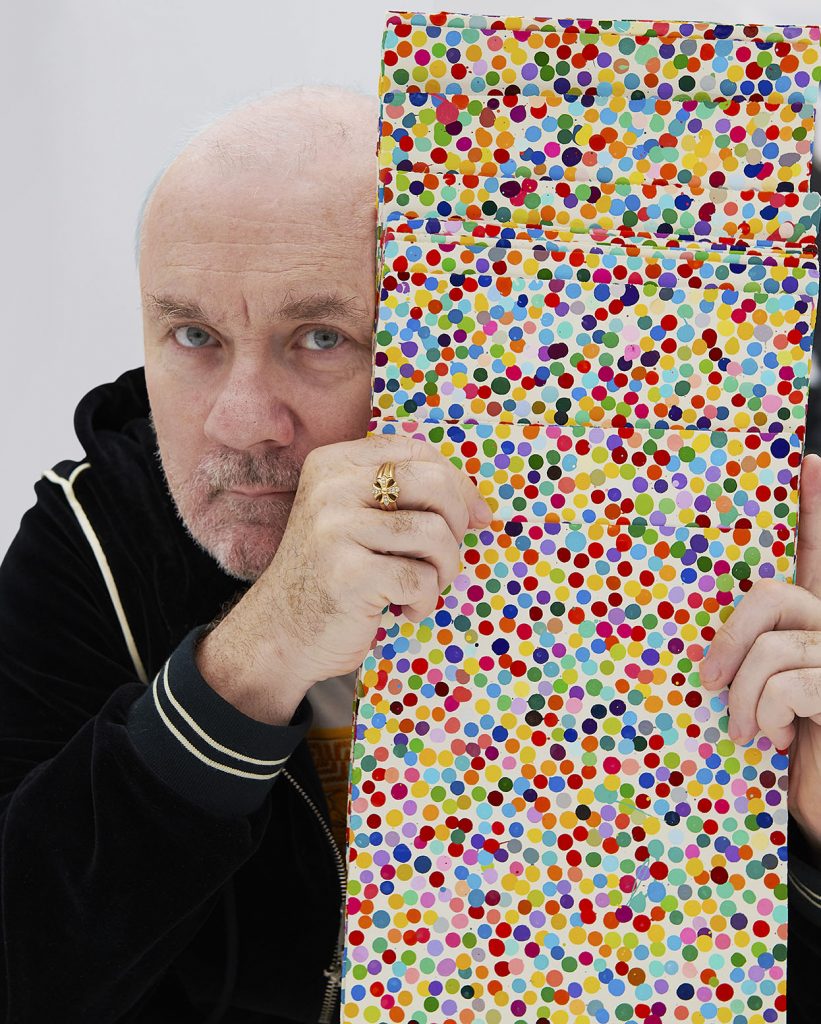

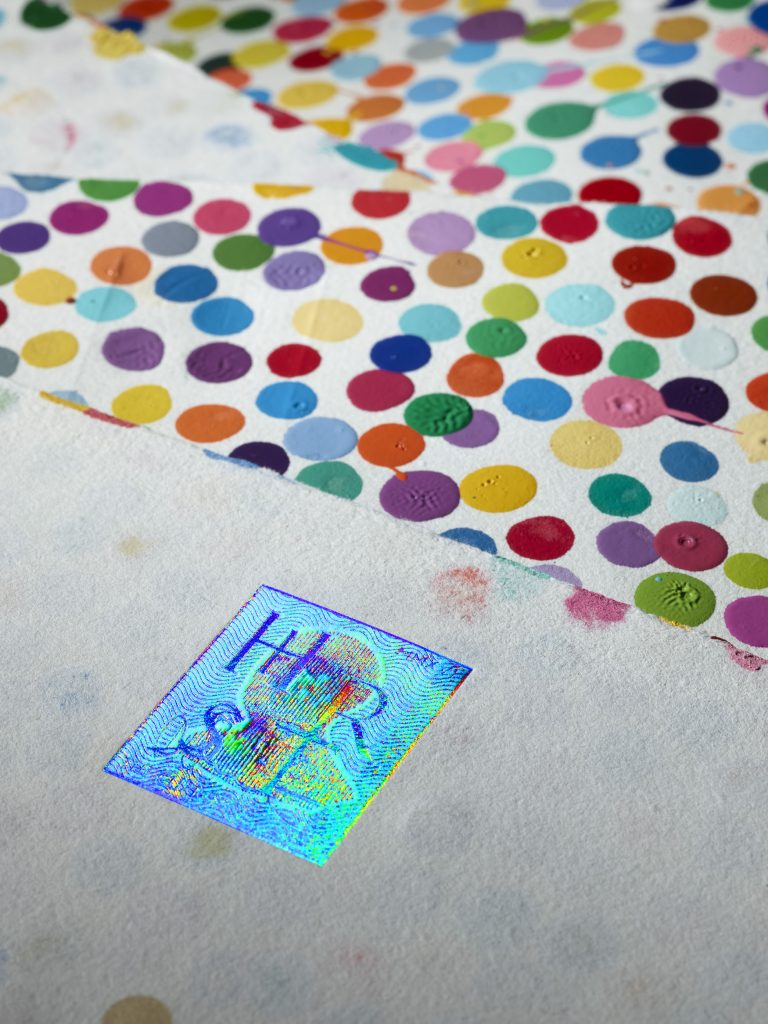

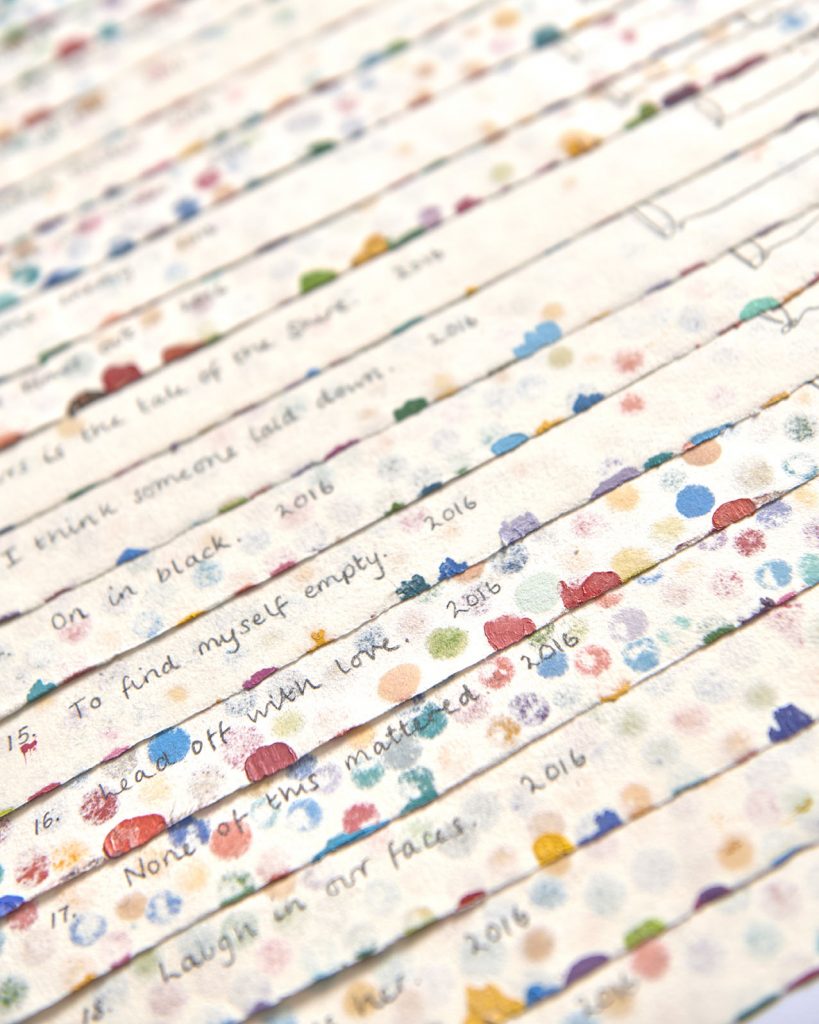

Instead of allowing it to lurk in the background, his latest work brings the tension between money and art to the fore. “The Currency” is the name for his drop of 10,000 NFTs, each tied to a physical painting created in 2016. After the $2,000 purchase of a “Tender,” as Hirst calls them, collectors will have to choose whether to keep the NFT, which will be a high-resolution photo of the painting, or turn the NFT in for the physical painting.

“The Currency” blurs the line between fungibility and non-fungibility, between money and art, and the project’s core choice will force each collector to make a value judgement between paintings in meatspace and NFTs. By nature, “The Currency” raises a number of philosophical questions: For starters, what is the value of the art versus the dollar value of selling it on the secondary market? What is the value of displaying it on the wall versus on a monitor? What is the value of portability versus permanence?

These complex, perhaps unanswerable, queries may be obscuring a more intimate one he’s ultimately posing to his audience, however: What am I worth to you?

First lessons

It’s like Isaac Newton getting bopped on the head with an apple: As Hirst was first learning about art, he was simultaneously learning about the art market.

Hirst often cites an early art teacher as a foundational influence — a “really great guy, a theatrical guy” who recruited him as Bottom in a school production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream; who fought valiantly to secure him a spot in the sixth form; and perhaps most importantly, who kept the classroom stocked with art auction catalogs.

“From very early on, I was looking at all the items on auction, which is a good way in, […] and I’d look at the prices, and I remember you could do like 10 grand, 20 grand for a Picasso or something,” Hirst tells Cointelegraph. “It wasn’t a lot of money, but to me, it was a lot of money at the time. Just seeing art and money in that catalog was good.”

In much the same way a happy accident helped Newton apprehend a fundamental law of physics, Hirst grasped early on that the attainment of fame in his field meant accepting and adapting to the reality that fine art and money are inextricably linked.

Today, his remunerative wizardry is widely renowned — even occasionally taking the spotlight from his work. He’s a master and a trailblazer when it comes to what crypto aficionados might call “pumpanomics” — the slurry of marketing, conceptual or visionary heft, and simple supply/demand mechanics inherent in scarcity that can make a project’s value soar to stratospheric heights.

Highlights include the 2008 sale of “Always Beautiful Inside My Head Forever” — a complete exhibition of 223 works that, in an unprecedented move, bypassed galleries to sell directly at auction for a staggering $200 million — and “For the Love of God,” a diamond-encrusted platinum cast of a skull that sold for $100 million to a consortium of owners that included himself. At multiple points in his career, he’s held the record for the most expensive work of art sold by a living artist; he currently sits in second place — adjusted for inflation, anyway.

“I mean, I worked out a long time ago that, you know, if there are two people with a lot of money, and there’s not a lot of something, it’s going to sell for a lot,” he observes. Where some artists accidentally ride Veblen curves to fortunes, Hirst constructs, aligns and launches himself from them like Evel Knievel.

Hirst and NFTs may be a perfect match for this experiment. NFTs, by simple virtue of existence, often set critics apoplectic — digital goods, they argue, don’t have “real” value. Or, by contrast, there’s an emerging faction of pearl-clutchers who say NFTs paradoxically have too much value — that they represent a perfect tool for the commodification and/or securitization of art.

And here’s Hirst, an artist who has faced similar criticism at both ends of the value spectrum, taking these liminal notions often floating at the fringes of contemporary fine art and concocting an experiment to force collectors and critics alike to choose.

“People get upset if I say, ‘My art is connected in a biological way to money.’ I just love it that people hate it. It just inspires me to do it. I want to look at it and see what happens. Will it do this? Can you push it this far without it breaking? Or will it break? I’ve done that in everything, in individual art and in this project.”

The “master of exponential growth”

In part, “The Currency” can be viewed as a response to a hypocrisy Hirst has been battling throughout his career — that art has always been “associated with lots of money” but “people weren’t really allowed to talk about it.”

“There’s the Van Gogh thing where you’re supposed to be a starving artist and you don’t make any money, never sell a painting. And everybody wants that. It’s a complicated thing. I mean, the thing about art is, it’s magic. You know, the whole thing is magic. You’re taking really cheap ingredients, and you put them together in a way that they become worth beyond their wildest ingredients. […] Alchemy. That’s what art really is.”

Viewers and collectors only selectively believing in the “alchemy” of art have long frustrated him — no one “looks at the ‘Mona Lisa’ and says, ‘That’s just 20 quid in canvas and paint’” — but by contrast, throughout his career, he’s often been asked about the prices of his sculptures relative to the cost of materials used to create them. It’s a false dichotomy that artists minting NFTs and dealing in digital scarcity are likely familiar with — and perhaps why Hirst was quick to embrace them as a medium.

“I don’t really know why, but I didn’t have that massive resistance that a lot of people I respect have got. I saw it as a really amazing thing. I saw it like the invention of paper. It’s like, you’re arguing about paper, like, ‘I’m not going to stop using papyrus!’ You’re already living in a world where you can have artworks, prints and editions, and it seems like now you can have artwork, prints, editions and NFTs.”

Part of the immediate comfort could be that Hirst intuitively understands digital ownership. He recounted a story about one of his sons purchasing $10,000 worth of digital goods in Clash of Clans, but even grown-up collectors are increasingly drawn to virtual expressions of ownership as well.

“In the world I was living in, where increasingly, I’ve noticed all art collectors are coming up to me, going, ‘I’ve just bought this, I’ve just bought this’ on [their phones], and you’re looking at Picassos and Jackson Pollocks, crazy stuff that they’ve got that’s worth huge amounts of money. And they’re sitting in bars, going, ‘I’ve got this, I’ve got this.’”

As a result, he’s now pondering whether digital or physical ownership is a more powerful psychological draw — and he’s eager to force people to make the determination:

“Looking at the NFTs and the actual artwork, I look at it and I think, ‘I don’t know, I’m excited by both, I don’t know which is most important.’ But then when I think about it, when I go, ‘What will people do?’ it sort of tells me where I lie, which is that most people will keep the [physical] art.”

An ironic element to the experiment is that Hirst freely admits that he’d be relieved if the project’s technical and market elements flopped. He tells a story about a collector who approached him once, griping that he was unable to sell a painting; Hirst thought to himself: Well, put it on the wall!

There is a universe where “The Currency Tenders,” instead of being fractionalized and digitized and widely traded and living forever on the blockchain, are simply framed and hung and enjoyed — as an artist, Hirst thinks that would be a comfortable place for the experiment to end. The risk for him is in “letting go,” in knowing that collectors may take, break, sell or even destroy his work.

Letting go also means that the project becomes something that is “alive” — trading, moving throughout the world in marketplaces, changing hands, reaching new audiences. This effort involves the brilliance of Joe Hage, who Hirst calls “the master of exponential growth.”

Hage, who was once described by ARTnews as a “significant but rarely discussed force behind the scenes,” is Hirst’s equivalent of a chief technology officer. Commanding a small army of data scientists, lawyers and smart contract developers, Hage — one of the partners of Palm, the ConsenSys-backed NFT-centric sidechain where “The Currency” will drop — tinkered with the specifications of the project to create what may turn out to be a generous drop strategy.

His team likely could have charged thousands more per “Tender” (Meebits, a project from NFT maestros Larva Labs, recently brought in over $70 million compared to “The Currency’s” $20-million sale), but for the thing to take flight, you need to offset some of that potential gain to collectors, who are then tested by thriving secondary markets. If prices do soar, it will tempt the greed of collectors, who will have to weigh potential profits — another key element in “The Currency’s” broader experiment.

Cults, gods and creators

Forty years after a child aimlessly flipped through a stack of auctions catalogs, in an innocuous former car park in West London, there is a temple being built to Damien Hirst. Palatial vaulted ceilings capped with translucent golden windows bathe the top floor with almost cathedral lighting (“‘An Almost Cathedral Light!’ Hirst bellows at this reporter from across the park, “I like that! I’m going to use that!”).

One day, it’ll be an excellent museum, perhaps Hirst’s equivalent of The Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh; for now, it’s one of the best private galleries in the world. When Cointelegraph visited, dozens of his cherry blossom paintings decorated the walls; French gallerist Hervé Chandès reportedly took one look and offered Hirst an exhibition on the spot. Hage notes that “less than 100 people in the world know this is here” — many of them, no doubt, took in all that beauty and ended up eager buyers of Hirst’s wares.

Religions need gods, cults need cult leaders, and often, cryptocurrencies need founders. The founders attend conferences — yearly ritual gatherings in the major capitals of the world — where they nourish the souls of their followers with announcements, announcements of announcements, roadmap updates, new white papers, and even, ever-so-rarely, genuine technical improvements that (even more rarely) might offer functional utility to crypto hodlers.

I am releasing “The Currency” at 3pm tomorrow (14th July 2021) on https://t.co/rO9nG5DgFa. This is my global art work experiment. It comprises of 10,000 NFT’s, each corresponding to a unique physical artwork made in 2016. Each artwork is called a “Tender”. @PalmNft @HENIGroup pic.twitter.com/ky3PbzmjhQ

— Damien Hirst (@hirst_official) July 13, 2021

In short, until the advent of decentralized finance and the birth of “productive” cryptoassets, buying a cryptocurrency meant speculators were buying a vision — a story about a possible future, often from a charismatic leader.

Set aside the artistic implications and take Hirst at his word, however ironic: He’s creating a currency. This is another powerful form of magic, one which even just a few centuries ago was the exclusive provenance of god-kings and emperors. As an artist and a modern icon, however, Hirst might be perfectly suited to launch his own.

For starters, when he talks about money, he talks like a crypto founder, eagerly citing David Graeber’s Debt: The First 5000 Years.

“It’s just amazing when you realize [money] is just trust. The debts get too big, then they wipe it out, and they start again, and the whole cycle goes over and over again, and people are getting ripped off continuously as well.”

He has a keen understanding of what Charles Eisenstein would call “Sacred Economies” — the knowledge that all money is ultimately backed by nothing more than a story — that “the proclamation that money is backed is little different from any other ritual incantation and that it derives its power from collective human belief.” While critics like to call Bitcoin an elaborate Ponzi scheme, in that respect, it’s not much different than the United States dollar.

Me, you and value

But what does this mean for “The Currency?” Which of the two forms of magic at play — money and art — is more powerful? Unlike a traditional crypto founder, Hirst readily admits his doubts. Since he first sold a piece for over 1 million British pounds, he told Cointelegraph, he’s wondered about the tenuous relationship between the two and claims that if he ever discovers the money is more important than the art, he’d “stop making it.”

“I guess I had a fear very early on that money was more important. And then, through that, I’ve always tried to challenge it. But when I sold a piece for 1 million pounds, I got total fear. I just thought, ‘It’s not worth it.’”

In a project that seeks to raise questions about the nature of value, about art and money, about the physical and the digital, this is the most important question Hirst is now asking his audience: What am I worth?

“Really, it’s like a test, isn’t it? You know, about that belief. It’s like, ‘Can you believe in me? Can you believe in this? Can you really believe in this? How long can you believe in me? Does it last; does it stack up; does it spread out?’ […] I mean, I don’t know where the art ends and the money starts or ends. The whole thing’s crossed over.”