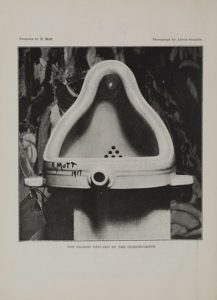

The most influential artwork of the 20th century, according to a survey of 500 professionals in the art world, disappeared from view in 1917.

More important to the field of art than any individual work by Warhol, Picasso, Emin or Hirst, it was likely thrown in the trash by the one person to photograph it.

“Fountain” was never even displayed at an exhibition; in fact, it was hidden behind a partition — shielded from view — despite the fact that its creator was a board member of the Society of Independent Artists that hosted the show at the Grand Central Palace in New York.

Marcel Duchamp was the artist, and a reoriented urinal signed “R. Mutt” was the titled piece.

The reason for the importance of “Fountain” to the art world is simple: it sparked an ongoing debate over what constitutes art.

The Independent’s Philip Hensher puts it more bluntly: Duchamp invented conceptual art.

Although the physical transformation of a urinal from one orientation to another may not seem particularly hard to master from a technical perspective, Duchamp argued that the piece was art because it changed the message from the physical object itself to the artistic intent of the creator.

“Mutt comes from Mott Works, the name of a large sanitary equipment manufacturer. But Mott was too close so I altered it to Mutt, after the daily cartoon strip ‘Mutt and Jeff’ which appeared at the time, and with which everyone was familiar. Thus, from the start, there was an interplay of Mutt: a fat little funny man, and Jeff: a tall thin man… I wanted any old name. And I added Richard [French slang for moneybags]. That’s not a bad name for a pissotière. Get it? The opposite of poverty. But not even that much, just R. MUTT.”

“Fountain” by Marcel Duchamp reproduced in The Blind Man, No. 2, New York, 1917. This file was donated to Wikimedia Commons as part of a project by the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Some art critics agreed. In defense of the piece, a dadaist journal published an editorial in which Louise Norton wrote:

“Whether Mr Mutt with his own hands made the fountain or not has no importance. He CHOSE it. He took an ordinary article of life, placed it so that its useful significance disappeared under the new title and point of view — created a new thought for that object.”

Over a hundred years later, the same debate

Blockchain artist Robness caused a stir in the crypto art community with his recent “Trash GIF” piece titled “64 GALLON TOTER.”

The piece was hosted by SuperRare, an online gallery that “makes it easy to create, sell, and collect rare digital art.”

In a story that sounds familiar, Robness submitted the piece, among others, to the SuperRare platform, tokenizing the works for sale to collectors. Smart contract technology “allows artists to release limited-edition digital artwork tracked on the blockchain, making the art rare, verified and collectible.”

Before long, Robness, along with his art, was removed from the SuperRare website.

The fascinating debate that has ensued doesn’t focus on black-and-white concepts such as right or wrong, but on whether Robness’s work is art. And just as importantly, who gets to decide?

John Crain is the CEO of SuperRare. He explains that a few months ago, Robness switched from tokenizing art that he created to art created by others. “For example, one week he tokenized both a Bitcoin logo and an Ethereum logo; images that were clearly pulled straight from the internet, and obviously not created by the artist.”

This breaks down the underpinning concept of SuperRare, which Crain notes is that “everything in the marketplace is original & created by the artist.” He is concerned that such a breakdown causes a negative impact on everyone in the ecosystem.

“So in this case,” Crain says, “our team had to make the rare and tough decision to suspend his tokenization privilege, and also remove from the UI artworks that he had tokenized since making the shift, which included the aforementioned logos and a gif of a trash bin from the Home Depot website.”

“64 GALLON TOTER” by ROBNESS

Let’s be clear: SuperRare is a private business and has every legal right to allow or deny access to its service. It also has a right to defend itself against potential copyright infringement claims, although in the United States Supreme Court case Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, Inc., it was noted that:

“The inquiry focuses on whether the new work merely supersedes the objects of the original creation, or whether and to what extent it is controversially ‘transformative,’ altering the original with new expression, meaning, or message. The more transformative the new work, the less will be the significance of other factors, like commercialism, that may weigh against a finding of fair use.”

Robness’s “64 GALLON TOTER” might reasonably be inferred to be transformative, but we must remember that we live in an era of SLAPP suits — strategic lawsuits against public participation — and global sales, often to residents of countries with very different copyright laws.

The artist’s perspective

The artist Robness reflects back on his experiences during the early stages of the crypto art movement. He explains that legal issues first came into play when certain members began copying and tokenizing art in a variety of ways. Yet, he was never concerned about the possibility of his art being copied, explaining that the original address for a tokenized piece is like the original paint on the canvas of a traditional work. “When people do the research and find where it first originated, all the other copies will be rendered moot.”

Robness points to the history of modern art for a comparison to the current conundrum. Famed 20th-century artists such as Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso had no qualms with recycling images into new and unique forms, creating a new artistic genre: collage.

Andy Warhol’s iconic “Campbell’s Soup Cans” painting is perhaps the most famous example of everyday objects being transformed into art, he says.

Despite this, Robness explains that pressures grew for platforms to be policed, with an effort to track down those who were copying others’ works. He questioned the notion, saying, “I’m not sure if that’s even gonna be police-able.”

One form of copying is called Marbling: copies of works are issued on collectible tokenized “Marble cards,” a practice that has drawn criticism from the community. Robness found the practice amusing, he says, feeling it was nothing worse than a fan paying homage to the artist.

“I said you guys can make Marble cards of any of my stuff. Make Marble cards of every single piece I’ve made, if you want to. If you want to spread it out there, go ahead.”

“I took a different path. It wasn’t in spite. It was just knowing the past history of how other artists became notable. At first you have to give yourself away a little bit to the public for them to just be able to see what you’re doing. If you start policing people right from the get-go, it leaves a bad taste in people’s mouths.”

Robness explains that he and fellow crypto artist Max Osiris fought against policing on the SuperRare platform, taking a “hard stance on it.” Soon after Osiris stood against the practice, he was removed from SuperRare, Robness says.

“He helped SuperRare. He helped contribute to the platform. A lot of collectors have collected him. Every single collector has his stuff. We’re the top two as far as collecting artwork.”

Robness reacted to the expulsion of his colleague with a protest: a series of artworks he describes as “Trash GIFs.”

“I started feeling for him being outcast, getting pushed out. Collectors started pushing out, so I started making art that was reactionary to that on the SuperRare platform.”

The Trash GIF movement

The incident spawned a series of simplistic pieces, produced in record time. “A lot of other artists in the space were dogging on some artists who used PhotoMosh, basically a glitch app where you toss a photo in and there’s tons of effects you can do and make some cool glitchy stuff within a couple minutes.”

Robness created the series of Trash GIFs “as a movement, as a type of expression,” he says. “I would joke, if you don’t make it in under 5 minutes, it’s not a Trash GIF.”

“So I was having fun with it. It was like punk rock, you know, I can make a song in under five minutes. It’s the same kind of concept.”

Again, the parallels with Duchamp are hard to ignore. Stephen Hicks, the author of Explaining Postmodernism: Skepticism and Socialism from Rousseau to Foucault commented that Duchamp’s work promoted a message more disruptive than the simple notion of imbuing an object with intent:

“The artist is not a great creator — Duchamp went shopping at a plumbing store. The artwork is not a special object — it was mass-produced in a factory. The experience of art is not exciting and ennobling — at best it is puzzling and mostly leaves one with a sense of distaste. But over and above that, Duchamp did not select just any ready-made object to display. In selecting the urinal, his message was clear: Art is something you piss on.”

Soon after putting up the “64 GALLON TOTER” piece on the site, Robness was removed, he says. “I got an email from John Crain telling me they had complaints from community members. He told me, ‘We’ve talked with our legal team and we feel that we have to let you go.’”

SuperRare removed the piece from the site, which technically, Robness says, means it is the first piece to have ever been removed from the collection, making it all the more significant.

Robness sees this as a sort of ironic and unique achievement. “If Marcel Duchamp is doing the urinal… I’m actually laughing. That’s like a trophy win for me, I’m not gonna lie.”

Robness argues that it’s too early in the movement to focus on policing and censorship. “I’m from the generation that saw the internet grow. It was a free-for-all.”

A similar movement is taking place today in blockchain, he says. “We’re supposed to be building a different world. The fact that some platforms are worried about suits and ties slapping them with lawsuits, I find that pretty ridiculous. It restricts a lot of important art that could be put out. These platforms should take a stance of protecting the artist rather than watching out for the collectors.”

Robness expresses concerns regarding the nature of the SuperRare platform. “We might have a centralized problem again like we do with the internet. There’s only a few on-ramps. We’ve got Google, Facebook, Twitter, Reddit, and a couple others, and that’s about it. I feel that for the Ethereum network, we might be having that issue as well.”

The gallery perspective

SuperRare’s Crain argues that the platform “provides a decentralized, peer-to-peer marketplace and exchange layer on which to trade artworks.” He points out that SuperRare is noncustodial and that “the artwork tokens will continue to live on Ethereum even if SuperRare were to shut down for some reason.”

Crain admits that there is currently a degree of centralization in the project. “The product design, the development roadmap, and who has the privilege to create art in the network as it grows, are currently determined by the team.”

He says that as SuperRare continues to grow, its goal is to “increasingly shift the most impactful decisions to be governed by the community, as we think that is the most sustainable way to grow to a massive scale.”

“But now while the space is nascent, our team is responsible for many of the crucial decisions which, we hope, will enable the digital art market to become increasingly legitimate and widespread in the next decade.”

The crypto art collectors

The heart of the problem, Robness says, lies with the collectors and their undue influence on curation. “I’ve noticed that collectors are having a lot of say and are pushing their weight… They’re ego-tripping a little bit.”

Robness describes an incident with a particular collector who, he alleges, flexed his influence to get Osiris removed from another digital arts platform, KnownOrigin. The collector threatened the platform, he explains, saying he would stop buying from it altogether if Osiris was not given the boot.

“I didn’t like that. I didn’t like how certain collectors muscled their way in.”

Robness acknowledges that curation is a necessary element of the art world. SuperRare, he says, has done an excellent job of finding a variety of artists. The platform offers art from a wide range of cultures and styles, with many different “flavors” to choose from.

While Robness continues to sell his work on KnownOrigin and via the OpenSea platform, he notes that “there might need to be new ways to get art out there.”

For now, Robness uses Twitter as his main method of promotion, but he recognizes that many collectors continue to go to SuperRare where most of the volume remains.

No hard feelings?

Robness does not appear to harbor any ill will toward the SuperRare team and its CEO. ”All props to John Crain and the team. They’re doing a really good job. I liked the platform from the beginning… I just think they should protect the artists a little bit more than watching out for collectors.”

For the movement to flourish, he advises SuperRare to tweak its approach: ”Let the collectors do their thing: let them buy. But don’t let them start curating stuff. Don’t let them start telling you what to do.”

Over time, the conflict may fade away, Robness hopes. For now, the movement is small and centralized hubs remain at the mercy of a few players. If platforms upset just one or two major buyers, the money flow stops, he says. “That could be a temporary problem because there’s not a lot of collectors in the space to provide competition.”

Robness is convinced of the significance of crypto art’s entry onto the digital stage. “It’s probably one of the most important movements in the history of art. It’s like the before and after stage: the transmission of it, the collectability of it.”

“I wasn’t an art collector before this. A lot of people are forgetting that. I love art, but I never bought pieces to stick on the wall. And here I am, I’ve bought pieces from Coldie; it was the first $1,000 piece and I just had to get it. I never did that in the old art world.”

What exactly qualifies as art may remain as unclear today as it was a century ago, but blockchain technology is set to open the world to a new and widely accessible form of expression, Robness believes.

“I think about the future, like, how many collectors will there be? There could be millions. That’s amazing. I think about that stuff all the time.”

Editor’s note: Robness writes in all caps. We have altered his chosen sentence case in written communications to make them more readable.

Because irony.