Ask any politician, parent, or social scientist: getting people to change their behavior is hard. The default setting is business as usual, carry on doing things the way we’ve always done them. And changing that takes directional applied effort — Newton wasn’t wrong.

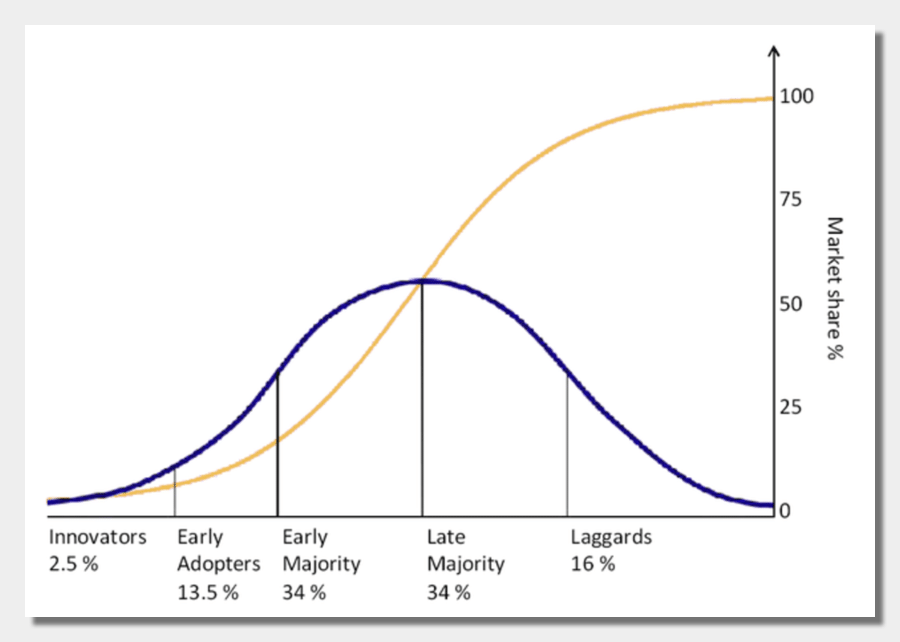

The more entrenched the original behavior, the more difficult it is to shift people out of it. And it can take a combination of different influences to trigger the transition, to push people along the adoption curve — which is also known as the Technology Adoption Lifecycle, or the Diffusion of Innovations, which was originally described in the 1960s.

Technology Adoption Bell-Curve (Rogers 2003)

This model describes how new ideas and practices catch on, led by small numbers of innovators, then early adopters who follow them. Subsequently, the trend grows in volume to fill out the bell curve, with early and late majority at the center of it, followed by laggards trailing down to infinity on the other side.

It’s a powerful visual, not least because the curve reflects the effort level involved for those trying to drive change — it’s steepest when you’re trying to build momentum and bring the masses in behind the early adopters. Once you get past half way, it’s an easier, gravity-assisted ride down the other side (if you consider network effects to be a reasonable parallel for gravity).

Different people find their comfort zone on this curve depending on internal factors to a large extent — personal risk profile, attitude to change, and so on. But it is inevitably acted on by external events too, even if we think we’re deciding for ourselves.

Take working remotely, which was still very much in the early adopter phase until the beginning of this year even though the tech was all in place and the curve was starting to shift.

The promise of greater autonomy, productivity, and saved time and money wasn’t enough to encourage most people to try working from home — but the threat of a lethal pandemic was, not to mention the ability to keep working and earning money at all. Once people had no choice but to work from home, suddenly, the incentives were aligned like never before.

Notwithstanding the resistance that characterizes the laggard end of the adoption curve, there are large numbers of people and employers who now see this way of working as a long-term part of their ‘new normality’, with far-reaching consequences for business, travel, communities and beyond.

So, what about incentives to adopt cryptocurrency?

Diffusion and adoption of cryptocurrency

Bitcoin has been with us for over a decade, but most people would argue that we are still very much in the innovator phase. Right now there are a range of factors nudging new uptake, from what appears to be an imminent global economic crisis to a growing set of products and tools with improved user interfaces and ease of use.

The earliest innovators are motivated by the technology and the vision, and some can be quite disdainful of financial motives. But we’re hovering at the bottom of the steepest part of the curve still, and most people need incentives to get on board.

Aubrey Strobel is Head of Communications at Lolli, a platform rewarding online shoppers with Bitcoin on a wide range of sites presently oriented at U.S. consumers:

“Lolli is for a lot of people their first Bitcoin wallet, the first time that they’re owning Bitcoin. And it’s a very easy on-ramp for them because they’re not changing any behaviors, they’re just shopping online, and so long as they click to activate our browser extension, they’re passively earning Bitcoin on purchases they would have made anyway.”

Stacking sats without trying

Passive is surely good, when it comes to changing behavior. Smoothing away friction, with the Lolli extension running in the browser, means that people don’t have to create new accounts to use it at each retailer — it takes just one click to opt it in when they arrive at the site.

“Most people will never (now) learn to mine Bitcoin. And it’s still a low proportion that will ever go on an exchange and be their own bank — most people wouldn’t even know how to buy a stock”, Strobel explained. “More might buy somewhere like Coinbase, then try to figure out how to move and store it safely, but with Lolli people just accumulate Bitcoin without trying.”

This should mean that more people are motivated to then learn about storage and what to do with the satoshis (or sats, the smallest fractional unit of a Bitcoin) they have stacked once they’ve acquired them. Strobel recognizes this as the next thing the platform needs to provide. “Actually a very low percentage of people are cashing out, so we need to teach them how to hold their money. We want to partner with a few wallets, and the next step is to teach people how to properly manage their assets.

“We’re doing this through our blog, quick bits of content that explain Bitcoin, and its positives and negatives. We’re coming up on our second anniversary in August, so I think it’s time for people to start moving and owning their balances, especially if they’ve accumulated quite a bit.”

So it’s all about incentive. Learning about self-custody and storage might feel like a step too far up the learning curve when it’s all theoretical, but when you’ve actually got some Bitcoin of your own to manage, you have some motivation to hang on to it safely.

This leverages the well-known cognitive bias of loss aversion, which dictates that we’re far more reluctant to let go of (or take risks with) what we have, compared to intangibles and theoretical benefits.

Incentivizing positive action

Another startup, a bootstrapped international collaboration called sMiles, aims to go one step further in behavioral nudging by encouraging pro-social activities in exchange for crypto, rewarding actions like walking and running — and even driving, for smaller rewards. Still in beta, sMiles (“sats for miles”) also incentivizes viewing of ads and playing games to encourage users to accumulate sats and fund the development of the app.

Founder Igor Berezovsky has been interested in monetizing attention and healthy behavior for years, but it’s only the combination of tracking technology like motion sensors in smartphones and smartwatches, combined with the existence of Bitcoin and the lightning network, which makes it possible. And while the rewards are small, it’s the promise of appreciation in a hyper-bitcoinized future which offers intriguing promise.

As Berezovsky said, “If I am going to buy some Nike shoes for $100, and a company offers me $2.00 cash back, that’s not going to change my life. But if the possibility of hyperbitcoinization is there, you could say that in eight years you effectively got those shoes for free. Even if it’s a low probability, this basically makes Bitcoin and sats the best possible tool for incentivizing people now.”

At least for incentivizing people with a long time horizon, who would have resisted the marshmallow with their eye on the greater prize.

And like Lolli, the app does not require any technical expertise or crypto knowledge to set up and run, while it lets you accumulate rewards for the things you’re doing anyway (engagement with ad videos being entirely optional, on top of the sats for simply moving around).

Berezovsky is keen to reward and monetize other kinds of interaction in future through the app too: “We believe that many small real-life actions could be economic transactions, such as sharing content, and even more non-digital actions. So many things can be rewarded, thanks to the lightning network which allows us to do really small transactions for almost free instantly, and be secure as well.”

Given the way we all continually leak data about things like this for free through our device and app usage, there’s a nice symmetry to the idea of getting paid for it.

Both models are also broadly based enough to cope with mass changes in behavior that we have witnessed this year, reflecting the way people are doing things differently over time. As Strobel points out, “Travel used to be our biggest category, but we’ve not been hurt by the lack of travel, because people are shopping for other things now, and more and more people are newly shopping online.”

The future is… rewarding

As evidenced by the fact that sMiles can track more miles spent in private cars than public transport, and Lolli is rewarding hodlers more on supermarket toilet paper restocks than long-haul vacations, everyday behaviors incentivized by sats don’t change in essence; only in context.

We’re likely to look back on 2020 as a year of pivotal change. Sometimes you can only identify these inflexion points retrospectively, and for people who suddenly realize what their sats are worth once we’re on the other side of the next big bull run, that might well be the case.

Everyone in crypto today has had to overcome obstacles. They engaged in self-education, avoided the scams, and embraced something completely new. Everyone you meet in this space, at least so far, will probably be able to pinpoint the moment of their epiphany, when they first ‘got it’, and grasped (or at least glimpsed) the real potential of decentralized non-sovereign currency.

But everyone in crypto tomorrow… that’s a different story.

Will the development of aligned incentives be the nudge that new users need to get on board with cryptocurrency?