For years the crypto industry has clamored for more attention from institutional investors. Big name investors are seen as a legitimizing force that will help open the floodgates for capital, and the doors to greater adoption.

However, that is just one side of it. Fund managers have one primary responsibility — making money for their partners and shareholders. For some that means building.

And for others… well, there’s more than one way to profit from a volatile market.

The recent publication of the short thesis on LINK by Zeus Capital, has brought the term “activist investor” into the crypto spotlight. More on that later. As one of the most powerful terms in traditional markets it conjures names like Carl Icahn, Bill Ackman, David Einhorn and Dan Loeb. These are powerful figures who changed things in dramatic ways for the companies that came into their sights.

If the crypto industry is in fact about to see the rise of the activist investor, the space may be in for a shock. There is a reason for the adage: “Be careful what you wish for.”

Who is the activist investor?

According to Investopedia an activist investor is:

“…an individual or group that purchases large numbers of a public company’s shares and/or tries to obtain seats on the company’s board to effect a significant change within the company. A company can become a target for activist investors if it is mismanaged, has excessive costs and could be run more profitably as a private company or has another problem that the activist investor believes it can fix to make the company more valuable.”

A good example of activist investing was the fight for control between Jeffrey Smith of Starboard Value and Darden Restaurants (Olive Garden, Capital Grille). The activist investor had ideas about how to improve the company, but the board disagreed. In the ensuing fight, Starboard Value launched a massive campaign to highlight the shortcomings of the company, and changed the composition of the board. As a result Darden Restaurants prospered.

However, it is important to remember investors are driven by profit opportunities, and that doesn’t always mean rebuilding; sometimes it’s about exposing and watching something crumble. A prime example of that is Bill Ackman’s fight vs municipal bond insurer MBIA. Bill Ackman took a short position and published a negative report highlighting the issues with MBIA. In the end he profited to the tune of over $1 billion dollars.

So what does that mean for the crypto industry?

The crypto industry is evolving in such a way that it must make the activist investor salivate. The two key ingredients are easy publicity, and the ability to make proposals and ultimately affect operations of a project.

Given how quickly FOMO and FUD spread across the industry, activist investors should have no problem making their message heard. Social media has evolved to the point that rumor and news are virtually indistinguishable by less-sophisticated participants. In fact even the most academic and thoughtful investors often have to perform forensic-style analyses of stories in the Twitterverse in order to parse fact from fiction.

The point regarding proposals is more nuanced. While projects are not public companies (and many are not even private companies for that matter), some are implementing a decentralized autonomous organization (DAO) governance structure. While specific details differ, the basic premise is that token holders get to make proposals and vote on proposals that impact the project, network, and ecosystem.

Decentralized governance may be no protection

Decentralized governance was introduced in order to ensure that the project is community-owned and its development is not under the control of one entity. We have already seen votes in MakerDAO to expand the collateral base and in Compound to change the token distribution model. For the most part these have been considered as beneficial changes: but what if an activist investor sees a profit opportunity that may confer no benefit to the long-term health of the organization?

It might be argued that for some, this is just a clever way to circumvent regulation and issue unregulated securities. Investors have suggested that the governance tokens can be seen as stocks without dividend. Holders have the right to vote and (this is critical) may vote to distribute dividends at a later date.

So, an activist investor may propose to distribute network fees as dividends, perhaps at the cost of network stability or regulatory scrutiny, to exercise short term gains. For many projects an activist investor would only need to convince a few parties.

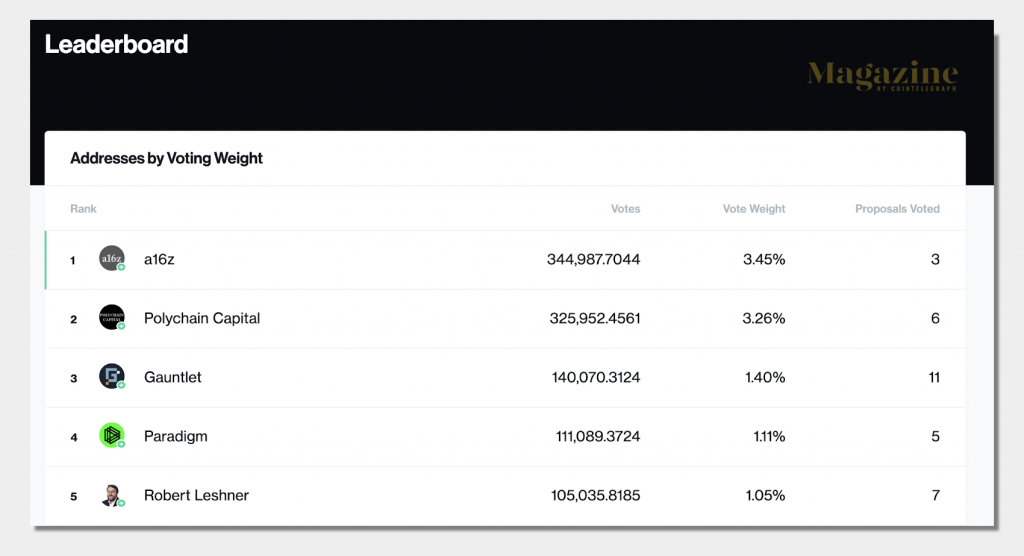

Source: https://compound.finance/governance/leaderboard

For example, of the top five shareholders on Compound four are funds (and the fifth is the CEO). Given that for a proposal to pass it needs a majority of 400,000, it’s conceivable that some funds could push through initiatives that are profitable to them with little opposition.

Show us the money

For now, the industry sees the investor-project relationship as “what is good for the project is good for the investor”. However, this does not always work in reverse. Investors are looking for profit, and if they disagree with the founding team, they may act to replace it.

For instance: IOHK, the company tasked with development of Cardano, is under contract until the end of 2020. In theory an activist investor may disagree with Charles Hoskinson’s vision for Cardano, and launch a campaign to vote in a new development company. If this were to be successful, it could potentially introduce massive changes to the network.

Note that in this hypothetical scenario neither the individual investor nor even the fund or group they represent may have the ability to change governance using their own stakeholder power (after all, Hoskinson is clear that Cardano is being developed to create a truly decentralized governance model). But the point is that they might seek to convince others to join their quest to replace IOHK, and in an age of social amplification — and an industry so attuned to it — they might even be successful.

Similarly, for DeFi protocols, if a fund with banking ties comes in and decides it wants to take the project private or institutional, it could theoretically push through proposals that could be as radical as implementing KYC.

It is all about profits. The widespread pump-and-dump schemes during the ICO boom have shown that despite grander goals articulated in white papers, money rules. If an investor believes that a short will increase profits, he or she may convince other investors to go along with the plan, even if it undermines the long term future of the project.

Isn’t shorting a token just FUD?

The story with Zeus Capital approaches investor activism from a different angle.

First let’s note that the origins of the report are shrouded in mystery: Zeus Capital may or may not be a real firm; their descriptions of Chainlink’s potential may or may not be accurate; a research organization may or may not be behind the document. Instead of focusing on the veracity and accuracy of the report (refer back to that forensic analysis I mentioned earlier) I’ll focus here on what appears to be its intent, and the response to its publication.

The report is trying to expose inadequacies with the project to profit off a drop in price. The move elicits memories of Bill Ackman’s famously public short of Herbalife. Fans of Chainlink may find solace in the fact that Herbalife is still standing.

Still, it is important to understand that a public short is different from a FUD campaign. The chief difference is that the first is (supposed to be) rooted in facts. Zeus Capital presents an articulated thesis, with the apparent support of on-chain data analysis and ecosystem research. Furthermore, it evaluates the “fair value” of LINK instead of just claiming that the token is “worthless”, although a price target of $0.07 issued while the token trades at around $8.00 is aggressive. The report is designed to resemble a traditional industry approach (see Is MBIA Triple A).

It’s notable that the response to the report has been primarily driven by investors who are considered to be long on Chainlink, and amplified via social media platforms such as Reddit and Twitter. These investors reject the central thesis of the report, and focus on the notion that it has been created in bad faith. It’s also worth noting that the so-called ‘Link Marines’, an ostensibly loose coalition of boosters, have relentlessly promoted the value of Chainlink’s LINK token for months.

So the battle for the price of LINK rages on. If the Chainlink thesis proves accurate it may embolden other investors to poke holes in young crypto projects. With some projects sporting relatively high valuations (the LINK token has a market capitalization of over $2.75 billion at the time of writing) this may cause a shorting trend.

Illiquidity as a virtue

For once, poor liquidity helps crypto. It simply isn’t that easy to accumulate a large short position in a given asset. As noted by Katerina Stroponiati, Founding Partner at Monday Capital:

“The majority of the crypto projects lack basic fundamentals. If the tools were available to short a token, we would happily speculate against it. But in order to do so properly (short on margin for example) you need:

- Tools (currently being built, see VEGA for example) and

- Meaningful liquidity (in some projects there is not enough to bet against).”

Furthermore, given whale dominance in most project ecosystems, a public short is likely to suffer heavy losses from a short squeeze. Whales will simply take the opposite side of the trade.

Moreover, many project communities have a fiercely loyal base. The stout support that Chainlink, XRP and others receive is not always rational. These supporters are likely to give projects the benefit of the doubt and time to fix minor flaws.

In fact, added scrutiny from activist investors may benefit the industry, and some like Mike Alfred, co-founder and CEO of Digital Assets Data, see their emergence as a positive:

Good governance and accountability is hugely important for the long-term performance of any company, network, or asset.

However, the risk here is if a major project is discovered to have serious issues it may cast a shadow over the entire industry. Chainlink, to continue the example, is now a top ten project on CoinMarketCap and something of a poster child for the supposed rise of application layer projects among a market dominated by protocols.

If it were found to be misrepresenting itself, with founders profiting at the expense of retail investors, this could be an Enron-like event for the industry. It would undoubtedly draw the attention of the mainstream media and regulators, and could very well result in capital shortage for other emerging projects.

Ultimately, the industry should take notice of the Zeus Capital report. Remaining agnostic regarding its provenance, it’s a calculated play to expose real or imagined frailties in a major crypto business with a view to profiting handsomely from a short position.

If the industry continues to grow, activist investors will come looking for profit. That means it is time to think about governance and asset value in a pragmatic sense.

Baron Rothschild supposedly noted that one should “Buy when there’s blood in the streets”.

If activist investors are sharks, he could just as easily have said blood in the water.