“They say when you’re offered a seat on a rocket ship, you don’t ask, ‘Which seat?’ You just get on the rocket ship and hold on for dear life. So that’s what I did.”

For Alex Tapscott, it’s been an exhilarating ride ever since the publication of “Blockchain Revolution”, a foundational work on the technology’s far-reaching possibilities. The co-author of the book and co-founder of the Blockchain Research Institute (BRI) says his success stems from a family effort.

His parents have been a huge influence in his life, both as leaders in their respective fields. His mother, deeply involved in politics and not-for-profit organizations; while his father is a respected author and technologist. Alex explains that his father, Donald, quickly realized that personal computing and the Internet would have an outsized influence on business and society.

“Dinner table conversations were hardly ordinary. We didn’t talk about the weather very much.” Tapscott explains that his parents would challenge the kids. They were expected, even at a young age, he says, to have an informed perspective. “As a kid, not a lot of grown-ups care, frankly, what your opinion is on matters of the day and my parents did. Having that in the household was a very positive force for me.”

A typical dinner conversation in the Tapscott household might involve discussing “systemic forces or economic forces, or models of how we organized society.” Sometimes the discussions would center on certain people or events “and random things that occur that change the direction of things.”

Tapscott’s father would often describe history as a series of class struggles, while his mother focused on key events, and individuals who shaped history. Tapscott says he has gleaned insights from both of his parents to formulate his own view on why things happen the way they do, and where the world is going.

Sports and leadership

Tapscott was not a straight-A student in high school, he admits. “I was always a really good student in things that I cared about and a pretty mediocre student in things that I didn’t care about.” He got better as he got older, he says, “which is, generally, a good trajectory to be on.”

As a rambunctious student, Tapscott explains he was fortunate to have teachers and coaches who figured out how to channel his energy positively through organized sports. He was the captain of his high school football and rugby teams, playing hockey and other sports on the side. His passion for sports continued into college, and he represented Canada on the national U-21 junior rugby team. The experiences gave Tapscott the opportunity to “flex the leadership muscle.” He feels organized sports offer young people a chance to learn from having people “follow you into battle,” providing leadership opportunities.

“I was always sort of a different person in math class than I was on the field. I was a very serious person when it came to sports and not always that serious when it came to academics.”

But one particular rugby and football coach also happened to be Tapscott’s math teacher. “He was able to challenge me to always do better.” Tapscott admits he was not always the best math student but because of the positive relationship he enjoyed with his coach, the teacher could “bust my chops and crack the whip” in class.

“It’s really important when you’re a kid to have a goal to focus on, something that’s maybe bigger than yourself. That’s something teams always did for me, which is to make sure you look beyond yourself towards a common goal.”

AC/DC: Amherst College / Duke or Columbia?

Growing up in Toronto, Tapscott says he had high aspirations for his upcoming post-secondary experience. The few intellectual super-freaks, he says, might end up going to Harvard, Yale, or Princeton but most kids would go to nearby universities like Queens, the University of Toronto or McGill in Montreal.

Tapscott thought he would likely go with a local option, but his football coach encouraged him to see if he could gain interest from some American schools. One guidance counselor advised him to look into some smaller liberal arts colleges. “Everyone’s heard of Harvard and Princeton and Yale and Columbia, but there are these other schools in New England that are just as good. They’re way smaller, they’re as hard to get into, and they offer a very different kind of experience.”

On a whim, he and his father put together a highlight reel of him playing football, set to AC/DC’s “Hell’s Bells.” They sent the video to Duke, Columbia, Amherst College, Harvard, and others.

Columbia University and Amherst College reached out. Columbia University, in Manhattan, couldn’t be more different from Amherst, “a school in the middle of nowhere,” he says. Tapscott flew down to Amherst, met the team, sampled some classes and attended a few parties. “I got a really good vibe from Amherst.” He figured he would probably spend a lot of time in his future in places like New York and wanted to try this “quintessentially American small-campus experience.”

“Amherst College is a tiny liberal arts school in western Massachusetts… But it’s also produced one president, three Nobel laureates, literary geniuses like David Foster Wallace, and hundreds of other really important people in the United States.”

“So, I got in, largely because I was a good football player. On my academics alone, I don’t think I would have got that.”

Tapscott finished at Amherst with a degree in a major that is unique to the college: Law, Jurisprudence and Social Thought, a hybrid of political science and legal philosophy. “That was very cool to do, but it did not prepare me, at least I thought initially, for a career in investment banking because I didn’t have the practical basic skills like financial analysis and accounting and things like that.”

“But it turns out that if you’re curious and you like learning about one thing, you can learn about the other thing. So I picked that up pretty quick.”

My father, the author

When Tapscott graduated from university, he wasn’t yet sure what he wanted to do with the rest of his life, but he knew that like his father, he enjoyed writing. “For my undergrad, I did an elective thesis where I wrote a 120 page thesis, so it wasn’t something that was totally foreign to me, but I never thought of it as a career.”

After graduating, Tapscott went into investment banking. Canaccord Genuity, the largest independent investment bank in Canada, recruited him on the basis of his strong academic background at Amherst. “The people there had met me before and they were just willing to give me a shot, basically.”

Tapscott spent eight years in investment banking, working with institutional investors, mutual funds, pension funds, hedge funds and large family offices that were primarily allocating capital in the Canadian markets. “It was pretty typical bread and butter investment banking type work, but it was all new to me when I started.”

It’s not that he was trying to do something different than his parents, he explains. “I just wanted to try my hand at something that I’d heard was really interesting. And it was.” The job involved long hours and not a lot of warm and fuzzy congratulatory support, he says, but after surviving the first year or two, it became a very rewarding career. It also helped inform his thinking about blockchain, crypto assets and Bitcoin.

Tapscott modestly insists he’s not an expert. But years of experience, rigorous training as a CFA charter holder, and involvement in “hundreds of transactions, mergers and acquisitions, financings, bankruptcies and so forth” have given him a unique perspective. Extensive financial experience and a passion for writing and technology make for an interesting combination “which, I think, is why people like hearing from me.”

“I speak to a lot of bankers and executives who want to understand this technology better. I think I have some credibility because I actually worked in that business for a long time.”

Leaving investment banking

After several years in the investment banking industry, Tapscott says he paused and “took stock,” reflecting on what he had accomplished and what he wanted to do in the future. He had risen from assistant to director in the equities business and was in a comfortable position. Still, he did not think of his investment banking career as a permanent stay. “So I said to myself, ‘Is this your first job or the rest of your life?’ I decided it was my first job.”

Tapscott began learning about Bitcoin around this time, in late 2013. The more he looked into the technology, he says, the more he became convinced that it was the beginning of a brand new industry. He imagined that the technology that made Bitcoin possible could have a wide-reaching impact on a range of sectors. He considered the process of clearing and settling trades and all the intermediaries and middlemen that play a role and capture value in the process.

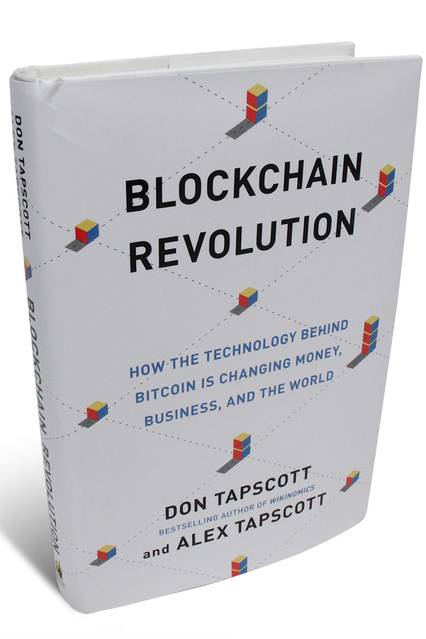

On a yearly ski trip with his father, the two discussed their interests. It didn’t take long before the topic of Bitcoin came up, as both had recently come across it. His father was running a research program at the University of Toronto as an adjunct professor, but nobody in the faculty had any practical financial services experience and a similar interest in blockchain technology. His father asked him to write a report for the project, which led Tapscott to write “The Bitcoin Governance Network.” The report addressed questions about governance, scaling and utility with the new decentralized resource. This work, he says, led to other research the pair did together, which eventually led to the book, “Blockchain Revolution.”

“My dad’s written tons of books, many hugely successful, like ‘Wikinomics’, ‘The Digital Economy’, etcetera.” Don Tapscott’s literary agent was interested in the new subject matter, explaining that nobody had written an intelligible book that explains blockchain to a generalist reader and business audience. The agent felt the father-son angle was an asset that could make the book more marketable. Soon, the pair wrote a book proposal and went to a publisher the father had worked with in the past. “They offered us a deal which we thought was more than fair.” The publisher would help fund all the necessary research and the work they needed to do to complete the book. “So, we got the deal.”

Tapscott did not want to leave his investment bank job before receiving his annual bonus, due to arrive months later. “So I hung around. I was writing this book proposal sort of in secret with my dad for the first four or five months of 2015. In June, I got paid out and the next day, I quit to write a book, which I’d never done before.”

His colleagues were stunned. “Some of them thought I was nuts. Some of them also understood that it was a really cool opportunity.” Had he left the job to go to a competitor, he says, his employers would have been very upset with him. “But you go to do something radically different, you go to pursue your passion, what’s someone going to say? They’re going to say ‘Good luck. We wish you all the best. We’re happy to support you.’ And that’s what they’ve done since.”

Father-son team

The pair spent most of 2015 writing together, finally releasing the book in May 2016. The timing, Tapscott says, couldn’t have been better. The book was released just as people started to care about the space, and it “ended up being massively successful.”

According to the publisher, Tapscott says, the book sold more copies than all other books on the subject of blockchain combined, and has been translated into nineteen languages. “You know, Mongolian, Romanian, Chinese, Korean, Japanese, etcetera. It’s kind of wild to see. I have all these copies of the book on my shelf. I don’t know how many copies we’re selling in Mongolia but it does exist.”

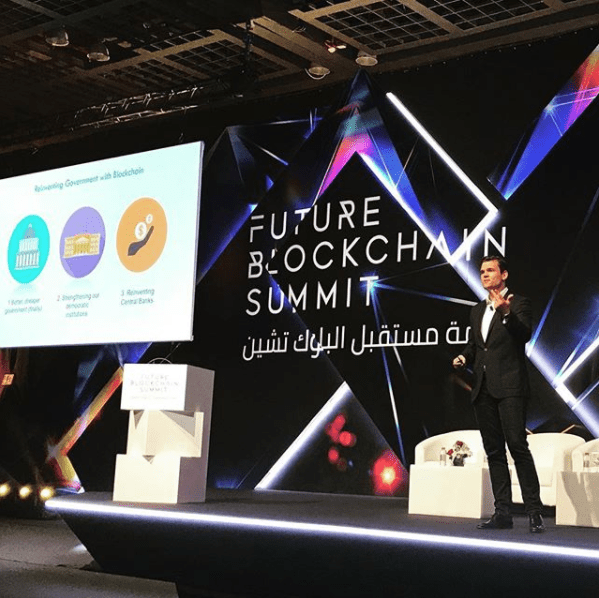

The success of the book presented Tapscott with a range of new opportunities. Since 2016 Tapscott says he has delivered more than 300 speeches around the world, visiting every continent except Antarctica. “But maybe I’ll get an Antarctic gig. We’ll see.”

Tapscott soon launched the Blockchain Research Institute (BRI), the largest independent blockchain think-tank in the world, funded mostly by large companies like Microsoft, IBM, FedEx, Exxon Mobil, Tencent and a number of governments. He spent much of his early days in the industry traveling and speaking to business leaders. The response was mostly positive. “People think big companies are hostile toward this technology. I think that, early on, they were just a little confused about what was what.”

The Tapscotts saw an opportunity to inform business leaders at large companies and governments about the use cases, challenges and opportunities of the new technology.

BRI would look into blockchain on an “industry-vertical basis,” he says, examining how it applies to “financial services, health care, energy, and so forth, but also how it would change the role of people within organizations.”

The program has been very successful and continues to accumulate new members as it diversifies. In addition to the core research project, the group also has an events business. The first flagship event, “Blockchain Revolution Global” was hosted in Toronto. The event garnered 1,100 visitors and 140 speakers. The plan is to roll out the event around the world, but the current pandemic situation has caused things to be held back, with the annual conference delayed until October 29-30 of this year.

Tapscott and his colleagues have also launched the Online Education Initiative in a partnership with INSEAD, the top business school in Europe. “We’ve developed a massive open online course which is hosted on the Coursera platform. As of today, we have over 25,000 learners.” Since the pandemic began, registration for the program has increased five-fold, he says. “This is a deep, comprehensive, two-month long course to learn about all the things that we do at the Institute. At the end, they have to do a practicum where they actually develop a use case and present it as if it was a VC pitch, which we think is pretty cool.”

Tapscott has also launched a book publishing business, and has recently released two new books. Alex edited and wrote the foreword to “Financial Services Revolution”, while Donald did the same for “Supply Chain Revolution”. They have “a couple more books” coming out soon.

Tapscott loses count as he mentally lists off the plethora of businesses that have sprung to life since the first book’s publication. “And what else? How many businesses have I talked about?”

He continues to travel the world, delivering speeches on blockchain. “It’s a diversified, multi-faceted business that is, at its core, focused on helping enterprises manage the transformation; how to adopt blockchain and not just survive, but maybe even thrive in this era of disruption.”

NextBlock

Following the tremendous success of the “Blockchain Revolution” book, Tapscott delved back into the world of finance, raising money to form an investment vehicle designed to seek out opportunities in the blockchain space. In the fundraising stages, Nextblock saw “tons of interest” Tapscott says, but news soon broke concerning marketing materials that were used in the funding process.

The allegation Tapscott explains, was that the company was misrepresenting the involvement of certain individuals in the business in slide deck presentations. “Early on,” he says, “we had conversations with a few people, some who expressed interest in advising. One individual we intended to reach out to, but we never got around to, was included in an early version of the slide deck in a group of advisers, along with a few others. Not all had agreed to advise the company.”

“In retrospect, looking back, it was obviously a mistake. We were moving really quickly to get to market and we were doing everything we could to keep our heads above water.”

In light of the allegations, the company was forced to cancel the main fundraiser. Ironically, Tapscott says, by the time of the formal fundraising road-show, none of the people concerned were still in the deck, but it didn’t matter at that point. “The perception was that there was something wrong with this company.”

With the latest funding round canceled, NextBlock liquidated the company assets and returned the invested money — along with substantial profits — to investors. Investors made nearly three times their money in a year and a half. “As the CEO, I ultimately took responsibility for the mistakes that were made by the company. As an act of good faith to all of our investors, I declined my share of the profits, which would have been around three million dollars.”

“It’s a decision I would make again in a heartbeat” Tapscott says. It turned a situation in which his reputation could have been damaged into one where investors in the business left with a better opinion of him. The company soon reached a resolution with Canadian and American regulators, paying fines with no additional penalties, which “put an end to it,” Tapscott says. As part of the settlement, Tapscott also volunteered to lecture university business students about the experience.

“It’s my responsibility to do what I can to clear the air. I’ve never been one to make excuses. I’m the first to admit that we were sloppy in our execution and we made mistakes.”

Next on the itinerary…

Tapscott is proud to talk about the latest book among his many projects, “Financial Services Revolution.”

“It’s a compendium of some of the best research that has been done at the BRI.” Tapscott wrote a substantial new chapter to the book. “It says ‘a foreword,’ but it’s 50 pages long.” The book was a bestseller on Amazon for a few weeks but is only available electronically for the time being. Despite the health crisis, the BRI is “humming along at full steam,” he says, continuing to grow. The all-digital model provides online courses, e-books, webinars, and research.

Tapscott has set his sights on a number of other projects, but says he will wait until the pandemic subsides before being more public or active about it. He is keen on finding ways to be helpful in funding and advising businesses that are using technology to create change in the world. “There’s so much opportunity out there. I expect that at some point, I’ll be doing that again.”

“But ultimately, the future is not something to be predicted at all. It’s something to be achieved.”

Tapscott explains that we are still in the early stages of this new industry’s development. “It’s everyone’s personal opportunity to be a builder, to achieve whatever future it is that you see for this business.”

“This is not something that is set in stone. This is the Wild West. It’s everybody’s opportunity to stake their claim and make it happen.”