I don’t remember my first personal email username.

I know the domain was with Pipex Dial, a U.K. provider to whom I paid a monthly fee for the privilege of receiving a unique string of abstract digits through which to receive email messages. I remember there were a scant handful of other early adopters who also had this thing. And I remember that it was complicated and expensive. But for some reason I’ve always been drawn to things like that.

My second email address, I remember clearly. Because the genius of Hotmail in 1996 wasn’t just the invention of email signatures and the first truly viral marketing campaign. The game-changing difference was that as well as giving away web-based email for free, Hotmail gave you the ability to choose any username you wanted, assuming no one else had grabbed it first.

Your real name, a nickname or joke, even businesses could easily get started with a free Hotmail email, at a time when owning an actual domain or website was still an obscure dark art. [email protected] got the world on board with email at last, and while the brand itself is now fully subsumed within Outlook, it endured for many years after Microsoft acquired it from founders Jack Smith and Sabeer Bhatia in 1997 for an estimated $400 million.

The history of web domains followed a similar path. While the domain naming system, or DNS, and first top-level domains were created in the 1980s, most early academic and defense applications relied on the accurate manual user entry of numerical IP addresses, and according to Wikipedia, fewer than 15,000 dotcom domains had been registered by 1992.

Fast-forward to the present day, and an explosion in new top-level domains, or TLDs, has enabled easy acquisition of branded and personalized online territory for any user, with the third quarter of 2019 alone seeing 359.8 million new domain names registered across all TLDs. Nowadays, our need to manually enter even the shortest and most memorable domains is diminishing in a world driven by the tapping of native app icons and voice search. Pretty soon, we’ll probably be able to instruct our devices and automated assistants by gesture or eye movement alone.

Until very recently though, cryptocurrency wallet tools have remained mostly in the “usenet” state of evolution, and there are good reasons why the security has had to develop ahead of the ease of use — if you mistyped an email or web address, the worst that could happen was an obscure error message, rather than the loss of actual financial value. But if personally identifiable email was the killer app that really created mass adoption of the internet, will personalized wallets be the catalyst for similar growth in digital asset adoption, even if we acknowledge that the stakes are significantly higher?

The access vs. security trade-off

No one can deny that the user experience of defining and accessing online territories has become simplified to the most basic level, but this has not come without cost.

Easy-to-use tends to correlate with easy-to-hack. Staggeringly large breaches of consumer data barely make headlines in the mainstream media anymore, and already in the first few weeks of 2020, Microsoft, LabCorp and even the United Nations have reported massive exposures of personal data in their care. New privacy legislation from Europe to California seems to have done little to protect users from such violations, and it’s unsurprising that identity theft continues to escalate globally.

In the fintech sector, traditional institutions are increasingly defending themselves from losses they have typically absorbed in the past, as they fought their private battles against hackers behind closed doors. If your online banking was compromised a couple of years ago, you’d generally have been made good, with any fraudulent transactions promptly reversed — even if you could never get a clear answer from your bank as to what exactly happened. Now, they’re cracking down on access standards, enforcing better practice from users with multifactor authentication, and even subjecting users to detailed interrogation about their password hygiene and personal information security practices.

This shifting of responsibility onto the user is an inevitability and a well-deserved wake up call for many, but some users need more support than others. It’s not OK that my elderly aunt uses the same grandchild’s first name as her password for everything, but due to branch closures, she has been forced into online banking on a PC that looks as old as she is. She never wanted to own one of these smartphones — so how is she supposed to implement the “strong customer authentication” being forced upon her by the institution she has trusted since her first wage slip nearly 60 years ago?

The bank has promised to work something out for her and are continuing to extend her full personal telephone support for now, but we’re walking a tightrope between user experience and security.

And the cryptocurrency world is treading similarly fine lines in the ongoing tension over the protection of privacy and uncensorability versus mass adoption.

We’re not talking about the needs of those like my aunt, who I probably have to accept is unlikely to ever get on board with crypto nor suffer unduly as a result. There is a huge mass of mid-to-late adopters way ahead of her on the curve, however, who are savvy enough to use password managers and multifactor authentication, and understand the consequences of irreversible transactions and personal sovereignty. Their growing uptake is essential for required network effects, but they are never going to get to grips with UTXOs and 35-character network addresses. So all but the most die-hard cypherpunk purists would generally agree that we need more accessible and easy-to-use tools.

Onboarding the next wave

A plethora of new services are emerging to improve the UX and make cryptocurrencies easier and more user-friendly for everyday humans while trying to ensure core security aspects are not compromised.

Bradley Kam’s Unstoppable Domains offers blockchain domains entirely separate from the current DNS, purporting to help provide uncensorable websites as well as payment tools for Bitcoin, ETH and Zilliqa.

Currently, you’ll need a browser extension to view content on the .crypto or .zil domains, and you won’t find them indexed by traditional search tools. However, the creation of a new network on an alternate root means only a little more friction, which most users should be able to handle — if they can see a good reason to bother. It all feels nostalgically 1990s, only without Geocities’ migraine-inducing color schemes.

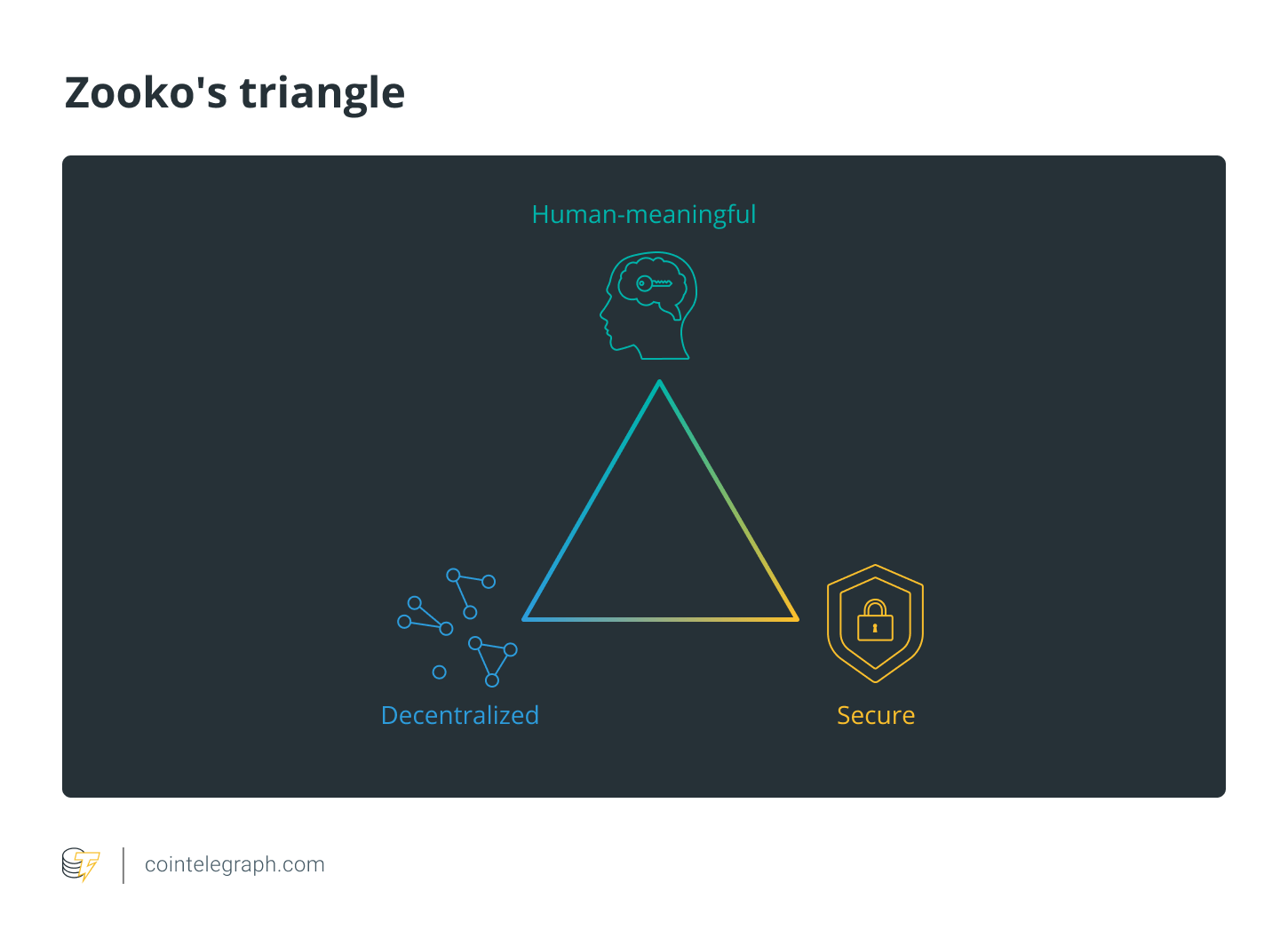

Namebase and its blockchain Handshake have focused on human-readable addresses, similar to those launched by the Ethereum Name Service in May 2017. The Handshake white paper references a trilemma known as Zooko’s Triangle (after the creator of Zcash), in which he posits that we can realistically achieve two out of three from the properties of human-meaningfulness, decentralization and security. (Some, such as the Monero development team who developed OpenAlias, and Nick Szabo, disagree.) The Namebase solution creates a single point of consensus around the association between names and certificates, using multiple actors to verify addresses on a blockchain in an attempt to resolve this paradox.

But this inevitably creates some degree of pseudonymization, and where there are any elements that can be reverse-engineered, any impression of anonymity is just that — a deceptive impression. So, are we in danger of creating just another kind of DNS under a different kind of centralized control? Is this trade-off really worth it in order to drive the mass adoption of cryptocurrencies?

I spoke to Emin Gün Sirer, presently on leave from Cornell University to work on Avalabs, about this complex intersection of psychology, security and usability.

“Human-readable addresses are nice, […] but in my opinion, nobody should be using anything human-readable anyway. Payments should be a secure channel between me and the merchant, the merchant giving me his address and me using it.”

This makes sense, as the DNS itself has always been easy to reverse-engineer, as Sirer pointed out way back in the 90s. DNS Security Extensions, or DNSSEC, is ICANN’s solution, with the addition of data origin authentication and data integrity protection to the basic address structure, but Sirer describes these efforts as “a supremely expensive failure of vision, a giant hole that ended up lining the pockets of a couple of vendors […] that has enjoyed zero practical adoption by the regular community.”

Unsurprisingly, he’s encouraged by the grassroots solutions emanating from the crypto community, which have the potential to rebuild a more secure and decentralized internet:

“They’re mostly young people, having no connection to the DNS community whatsoever, building an alternative secure system from the ground up using much more modern techniques. It’s a slap in the face to the DNS researchers who absolutely and unilaterally failed to fix this.”

A new decentralized structure for the internet of the future, which allows for human-recognizable transacting and navigation, sounds ideal. But in reality, the use of anything human-readable is, as Sirer indicated, easier to compromise. Tim Copeland of Decrypt recently proved the point, doxxing a number of high-profile people using ENS through careful analysis of their chosen Ethereum names and associated balances and transactions — after all, it’s all right there, on a public blockchain.

Exporing the human

It’s basic social engineering, the kind hackers have used for years — combining bits of information in the public domain with other facts people don’t consciously remember sharing, along with the odd (lucky and/or educated) guess, to join them together and expose connections that look nothing short of miraculous.

I saw a live performance by the amazingly talented British magician Derren Brown years ago, full of classy mind-reading stunts. At one point he “randomly” selected members from the huge theater audience and regaled them with facts about their personal lives and recent activities, striking enough home-runs to cause visible shock. Impressively, he had clearly memorized unique seating allocations for each night’s show, but a quick check on some of the names of people he singled out revealed completely open Facebook profiles, which specifically referenced their recent travels, injuries, meals and other explicitly mundane facts with which he astonished them. I’m willing to bet that each person chosen was also the named ticket purchaser for the event within their party.

It was a vivid reminder of how much personal information we all routinely leak into the world without a great deal of thought, and while I am busy lecturing my mature relatives about the reuse of passwords, people often reuse usernames, which are easily associated with their personal identity.

An example of this is Thorsten Schulte, @silberjunge on Twitter. Copeland found that “silberjunge.eth.” contained just $17 of Ether, and like many accounts, was probably set up just to experiment with the new service and explore what it had to offer when the Ethereum Name Service launched publicly last year. However, the address used to register this domain contained a more significant 1,163 ETH, and a further $121,000 worth of Ethereum-based tokens — perhaps something the owner may have wanted to maintain a little more discretion.

We all have different needs for personal privacy, after all, and often it takes a threat or a scare to make someone review and lock down their operational security. Bitcoin engineer and evangelist Jameson Lopp has gone to extreme lengths to protect his physical location and online activities after someone maliciously sent a SWAT team to his house. I used to have a limited company registered to my home address — until the day I attracted the attention of a far-right hate group by debunking some of their social media activities, and simultaneously learned that Google now thoughtfully supplied a street view photo of my home to accompany the search results for the business location.

As Sirer explained, this kind of social engineering is not the result of flaws within specific networks, but instead is a consequence of human behavior within an ecosystem of interrelated tools that can be interrogated in increasingly imaginative and granular ways.

“If I use my account to register my name for a conference, and then I use the same account to go and buy a name online, then there’s a linkable piece of information right there. So people use tricks like that, to de-anonymize. It’s absolutely not the result of ENS leaking any information, it’s the user behavior at the source.

“The bottom line is, it’s hard [to be completely anonymous and secure online], right? It’s twice as hard as keeping two separate wallets and never transferring money from one to the other. If you can do that, then sure, you can keep your anonymity, but most people find that too difficult.”

And that’s the rub, because for “most people,” it’s never going to happen. We need better tools that provide viable protection commensurate with the value of the asset being guarded — and in the case of crypto, also prevents access being accidentally lost forever.

Sirer points out that hardware wallets have not evolved or improved much in recent years, while mobile wallets are improving and offer real potential to extend highly accessible and acceptably secure tools to large numbers of users — including potentially billions of presently unbanked people, if not to my old aunt.

Exchanges are going to have to be recognized and regulated for the second layer they are becoming. We’re going to need DEXs — competitive with centralized exchanges in terms of usability — instead of what Sirer describes as the “horrible performance, absolutely horrible execution” of present offerings. He sees these improvements in the pipeline for deployment within the next 12 months, and they’re badly needed, given the transaction volumes they handle.

New money needs new understanding

Identity, trust, how we reveal and define ourselves to others; what we choose to share, to obscure or even hide in plain sight — these are complex and abstract concepts that are frequently taken for granted and unexamined in everyday discourse. Alongside the difficulties of defining what money and value really mean beneath the everyday distractions, this is part of the job the crypto community is going to have to do — help the majority overcome the inertia, habits and routines of the present paradigm.

But the crypto and blockchain revolution offers us a unique new opportunity to get things right this time — for a human-readable and human-centered future, which works as well for unbanked Gen Alpha kids as it can for elderly aunts. It’s a chance to build a Web 3.0 that may leverage biometrics and similar identifiers not reliant on memory, knowledge or description, yet does not compromise the original cypherpunk promise of user anonymity.

Resolving the puzzle of Zooko’s Triangle won’t be as easy as resolving a DNS address to a nice snappy URL. But it’s a challenge many of the brightest minds are working on: to create the mass-uptake, killer Hotmail solution we need for the future of money.