In looking to address low voter turnout and the difficulty of in-person voting for veterans and people with disabilities, companies have often advocated for the use of technology. Blockchain has been suggested as a solution to archaic voting systems, which could take the form of improving security by assuring that each vote is counted only one time, and is permanently recorded.

But the use of technology is not a cure-all, as anybody paying attention to the Iowa caucus debacle would know. And blockchain voting isn’t necessarily a perfect fix either.

Voatz, a Massachusetts-based company, has worked with West Virginia; Denver, Colorado; Utah County, Utah; and both Jackson and Umatilla Counties in Oregon, to pilot its blockchain-enabled mobile voting app. However, the company has met with criticism due to what Joseph Lorenzo Hall, senior vice president for a strong Internet at the Internet Society and former chief technologist at the Center for Democracy & Technology, described as the company’s “completely opaque” approach to security.

Although the company has shared an eight-page white paper and claims to have been audited multiple times, it has provided precious little information about what tests were conducted; what the auditors had access to; any vulnerabilities discovered; and whether or not they were fixed.

Last October, CNN revealed that a student security researcher was referred to the FBI over what the company says was an intrusion attempt—even though that research appears to have been protected by the safe harbor statement in the company’s bug bounty program. The bug bounty program terms on HackerOne were updated soon after the FBI referral made headlines, and first noticed by independent security researcher Jack Cable.

Referring researchers following terms of your bug bounty to the FBI isn’t cool. According to https://t.co/OIR3XXB0h8 Voatz director says the “live election system” was “out of scope”, but this was added to the terms today (https://t.co/60b4isZMZZ).

— Jack Cable (@jackhcable) October 5, 2019

In a statement to Cointelegraph, a Voatz spokesperson wrote, “As previously reported, Voatz detected and thwarted an unsuccessful attempt to gain entry to the system during the 2018 midterm election in West Virginia. As an elections company and conforming to the official ‘critical infrastructure’ designation under the Department of Homeland Security, Voatz reported the information about the incident to the West Virginia Secretary of State’s Office, which subsequently referred the matter to law enforcement agencies.”

Voatz CEO Nimit Sawhney’s comment to CNN in October was much more forceful. “We stopped them, caught them and reported them to the authorities,” he was quoted as saying.

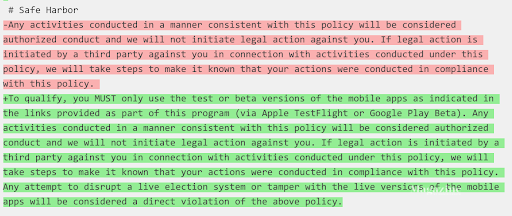

The alleged intrusion appears to be activity that’s protected under Voatz’s safe harbor policy, as written in HackerOne, which—at the time of the incident—stated:

“Any activities conducted in a manner consistent with this policy will be considered authorized conduct and we will not initiate legal action against you. If legal action is initiated by a third party against you in connection with activities conducted under this policy, we will take steps to make it known that your actions were conducted in compliance with this policy.”

Screenshot: https://hackerone.com/voatz/policy_versions?change=3620507

As Cable pointed out on Twitter, Voatz retroactively changed its policy after news about the FBI referral was public. The policy now reads:

“To qualify, you MUST only use the test or beta versions of the mobile apps as indicated in the links provided as part of this program (via Apple TestFlight or Google Play Beta). Any activities conducted in a manner consistent with this policy will be considered authorized conduct and we will not initiate legal action against you. If legal action is initiated by a third party against you in connection with activities conducted under this policy, we will take steps to make it known that your actions were conducted in compliance with this policy. Any attempt to disrupt a live election system or tamper with the live versions of the mobile apps will be considered a direct violation of the above policy.”

On Twitter, Voatz wrote, “No one who followed the policy was reported. The policy update…corresponds to the latest cycle (#3) of our testing. The previous cycle clearly listed the app links which researchers are supposed to use. You can view that in the history.”

But Voatz’s prior policy, as Cable pointed out, didn’t mention live systems, and simply stated that researchers should make a good faith effort to avoid privacy violations and destruction of data.

Voatz has pointed to voting as “critical infrastructure” as a reason the company felt it had to report the incident. However Kendra Albert, Lecturer on Law at Harvard Law School, said “I’m unaware of anything about the critical infrastructure designation that requires Voatz to report incidents to the FBI even if they thought they were malicious actions, let alone if they’re individual security researchers.”

The best practice for securing modern technology, Albert suggested, is to work with security researchers rather than referring them to law enforcement, which could make people less likely to report information that will help secure the product.

“Voters would have good reason to be nervous about a voting infrastructure that isn’t cooperating with security researchers who are trying their best to find holes before elections are tampered with,” Albert continued.

In an interview with Cointelegraph, Jack Cable said that bug bounty programs’ safe harbor policies are typically general statements rather than something this specific. “The fact that they added a sentence, ‘any attempt to disrupt a wide selection could be considered a direct violation of the above policy,’ that never happens,” he said.

In spite of Voatz’s denial, a reasonable observer might conclude that this change was made after the fact to make the student appear to have committed such a violation. Indeed, then-CNN reporter Kevin Collier wrote, “Sawhney told CNN the attempted intrusion he reported to the FBI was on its ‘live election system’ which was ‘out of scope’ for the bug bounty program.’” But retroactive updates to HackerOne program terms of services do not apply to research conducted before the change.

Professor J. Alex Halderman, who teaches an election cybersecurity course at the University of Michigan, has conducted extensive research on voter machine bugs, a subject on which he’s testified to the U.S. Senate Select Committee on Intelligence. Like other election security experts, Halderman has been critical of Voatz.

Is it possible that Voatz wanted to fire some warning shots to prevent University of Michigan students from conducting research about the security of its systems?

A Weak Defense?

Voatz does have its defenders, though the credibility of one of their more voluble advocates doesn’t rise to the standard set by security experts who have discussed the company’s product. One such person is Twitter user Tyler Dergen, whose feed largely comprises pro-Voatz tweets and retweets such as the one illustrated below.

Truly secure voting is in on the way — #Voatz is grateful to play a part in this important work in making #voting safer, more secure, and #accessible to all: https://t.co/gIWfbToVtf (@wroush via @sciam) pic.twitter.com/DeoZvek1rR

— Voatz (@Voatz) February 4, 2020

When Cointelegraph first accessed his LinkedIn account, the only other name under the “people who also viewed” section was Voatz CEO Nimit Sawhney.

What’s The Point Of A Bug Bounty, Anyway?

Researchers probing a system under a bug bounty are not generally required to register, says Albert. “The whole point of having a bug bounty program is so that you don’t necessarily have a conversation in advance with every person who may be doing something on your system,” they explained. “As long as they’re following the policy, they know that they’re in a good place with regards to potential claims regarding unauthorized access.”

And, Albert points out, if the students had read the bug bounty program as it existed from August 21, 2018, to October 4, 2019, they wouldn’t necessarily have any reason to think that these terms only covered the test app and that testing the live app wasn’t acceptable.

Additionally, Albert said, referring students and researchers to the FBI will mean that nobody wants to test these systems, making them less secure. The referral “basically tells security researchers who might want to investigate this company’s product, you can’t necessarily trust what we’re going to say about whether your testing is authorized. We may refer you to the FBI anyway.”

No charges appear to have been filed, but Albert said that even contemplating the potential for criminal charges can be a harrowing experience that may require students to retain attorneys and decide how they’re going to respond to an FBI request for information or warrants for their devices. “An investigation, even if it ends positively without charges, is a life-altering, totally consuming experience,” Albert said. “Turning [students] over to the FBI when there’s every indication that they’re doing good-faith security research consistent with your bug bounty policy is just inappropriate.”

Slow Bug Bounty Response Time

Cable himself reported what he thought was a fairly severe vulnerability to Voatz through its bug bounty in July. He received an email a few days after he submitted letting him know that the company was reviewing it, but says they didn’t actually confirm the vulnerability until almost a month later—a level of responsiveness that’s unusual, but consistent with Voatz’s secrecy about its app.

“Their response also felt insufficient,” Cable said.

The bug he submitted was for the Voatz Lite system, which is used for voting by web at universities, for example.

Although he says Sawhney promised to give him access for testing, Cable said that Voatz never followed through.

“It seemed like I could just cast the votes with an ID of a different user,” Cable said, “and it seems like it would go through.” The company denied that it would go through, but didn’t provide Cable evidence of that, and did not allow him to test it again. “I have no clue if this would actually work because they didn’t want to verify it. They told me they would give me a way to test it again, but they didn’t,” he said.

Whether apps are being used to tally caucus results or for voting itself, these tools must allow for robust testing and auditing—and yes, bug bounties—to increase the chance of finding and fixing any vulnerabilities before they’re exploited by those seeking to do harm. Companies should welcome security researchers, especially when their apps are utilizing newer technology, such as blockchain.

Promises of freedom to hunt for bugs should never be accompanied by prosecution for doing so—especially when the integrity of elections, and public trust in them, are at stake.