“Now is the time. If we can’t change now, we will never change.”

Yuzo Kano is frank in his assessment of the two thousand year-old Hanko tradition. “We need to revisit the historical role of Hanko in Japan.”

Hanko, or Inkan, is the Japanese stamp that’s almost ubiquitous in Japan’s work and life. Whenever buying a new house or car, submitting documents to a city government, or even getting permission from a manager for a vacation, Japanese citizens stamp their seal, or their corporation’s seal, on contract documents.

In a country that has been a standard-bearer for technology and digitization over the last fifty years, the Japanese maintain this analog method of conveying trust.

But now, imbued with renewed vigor due to the ongoing pandemic, those who want to update the Hanko culture are finding a tailwind.

As the coronavirus continues to wreak havoc on economic markets and redefines the nature of social interaction, Kano, the co-founder of Japanese crypto exchange bitFlyer and CEO of bitFlyer Blockchain, explained “I do think it is a strange thing to put your life at risk to use Hanko. It is a great time for Japanese society to rethink whether we really need Hanko. What, then, can be the alternative?”

Using Hanko means meeting someone in person: going outside when “staying home” is required. Research suggests that 46.7% of Japanese workers have visited their offices during the coronavirus outbreak specifically to use Hanko. It could even be argued that Hanko is one of the most important factors in Japan’s failure to transition to a functioning remote-working economy.

And this is a legacy issue: the Twitter-less Naokazu Takemoto, Minister of State for Science and Technology Policy, is the president of the pro-Hanko parliamentary group Hankogiren. During his inaugural speech he argued for “the coexistence of the Hanko culture and the digital culture” without explaining how this might be accomplished.

On a more progressive note, Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe recently ordered the Council on Economic and Fiscal Policy to push toward digitizing contracts and Hanko. Some private Japanese companies immediately announced that they would stop using Hanko, although a survey conducted in March 2020 by JIPDEC and ITR (a non-profit organization and a research company) found that only around 40% of Japanese companies have begun to digitize contracts.

Hanko and trust

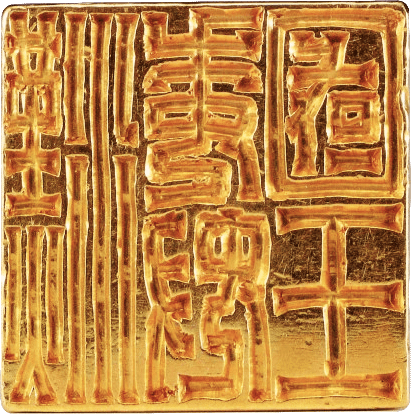

Hanko was a symbol of authority in China, and in the later years of the Han dynasty people wore Hanko emblems on their waist to demonstrate status.

In contrast, as Seiichi Monta points out in his “Hanko and Japanese”, Hanko’s imprint has conveyed “trust of character” throughout the country’s recorded history.

In A.D. 868, around the time many Japanese started using Hanko privately, Dajō-kan, the highest level of the Japanese pre modern government under the Ritsuryō legal system, defined the role of Hanko:

“The purpose of using the seal is to acquire trust, and to both publicly and privately dispel doubts of bad behavior.”

The oldest Hanko recorded is Kannowanonanokokuou-no-in, the golden Hanko for the King of Na, originating in China circa. A.D. 57 / Wikipedia

The oldest Hanko recorded is Kannowanonanokokuou-no-in, the golden Hanko for the King of Na, originating in China circa. A.D. 57 / Wikipedia

Monta illustrates the importance of Hanko to Japanese culture using the example of the International Military Tribunal for the Far East (the Tokyo Trials) after the Second World War.

Puyi, the last Emperor of the Qing dynasty and the Emperor of Manchukuo, a puppet state of the Japanese Empire from 1932 to 1945, testified at the trials regarding Japanese responsibility for war crimes.

One evidentiary issue required U.S. defense counsel Major General Ben Bruce Blakeney to establish whether or not Puyi had written the foreword to his private teacher’s memoir, Twilight in the Forbidden City. Puyi said he had never seen it before, and insisted that someone else wrote it. However, two of Puyi’s Hankos were stamped there.

In the end, Twilight in the Forbidden City was not accepted as evidence at the trial. According to Monta, it would be common sense for the Japanese to interpret the mere existence of the two imprints as proof of the author’s involvement. Monta concludes that Blakeney just didn’t understand the meaning of Hanko in the same way.

Blockchain and trust

Distributed ledger technology has been suggested as a remedy for hundreds of inefficient systems, beyond its popular incarnation as the underlying technology behind Bitcoin.

But if blockchain is to be successful in replacing Hanko, it must convey trust as Hanko has done for centuries.

“We often talk about reducing the costs of trusting others using blockchain technology”, says Hikaru Kusaka, the founder of blockhive, a company that aims to replace Hanko with a digital identity application called xID. “Ours is a society of contracts, after all, and you can’t just give others a verbal promise. Hanko has been there to secure trust.”

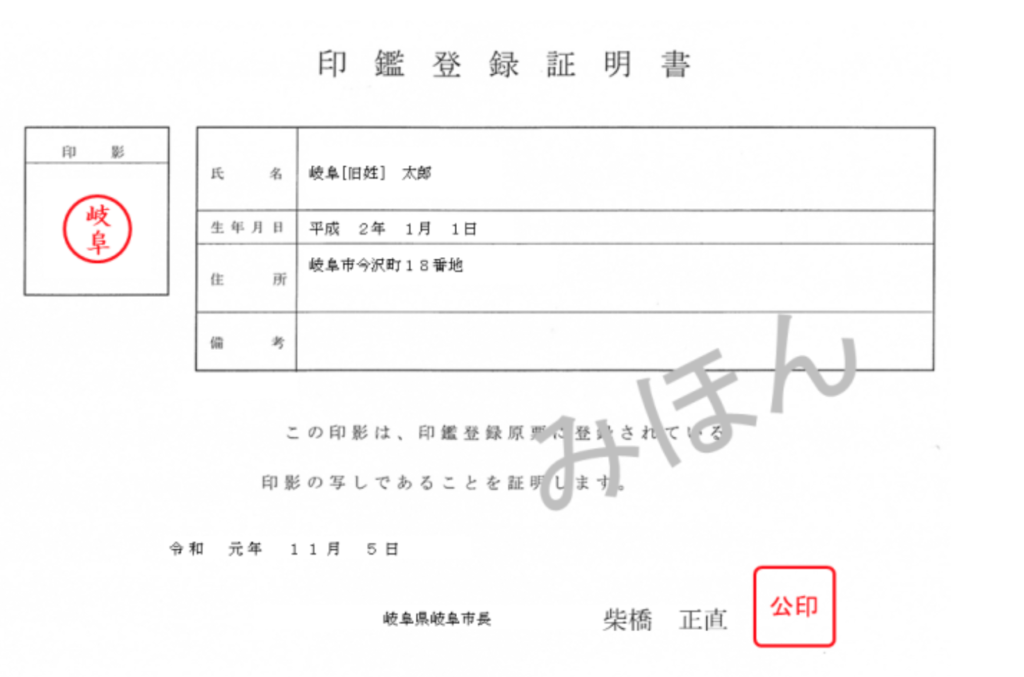

There are two types of Hanko: a private seal and a registered seal. A private seal can be bought at local discount shops and used without registration, while a registered seal has to be certified by local governments.

(Source: the city of Gifu)

(Source: the city of Gifu)

A registered seal is required for important contracts, such as buying houses. But Kusaka explains that blockchain can be used for creating trust without relying on specific central entities.

“To date, mutual transparency has been secured by third parties. Without a certificate issued by a public organization, Hanko becomes a mere carving. Blockchain can be used to prove trust in society.”

Meanwhile, Kano thinks it is best to start using blockchain for private contracts that don’t require the use of a registered seal.

“The point here is to avoid conflict. It is okay if both parties understand that they agreed on contracts. It is okay to use a private seal, a signature, a registered seal, or bPassport”.

bPassport is an app for users to manage their ID, addresses, and date of birth on a blockchain. Although there are many options to demonstrate consensus in the case of private contracts, Kano thinks blockchain is the strongest one in this instance.

“Blockchain guarantees that nothing can be erased. It is tamper-resistant and can demonstrate truth in a legal action.”

Blockchain can do more

But Kusaka claims that the blockchain alternative can go further than that. Hanko, by itself, can’t prove that the person who uses the stamp is its owner. He says there’s a clear analogy to using a house key; holding the key is not the same as proving home ownership. A CEO might give her Hanko to her sales team, and they might use her Hanko to enter into a contract.

In contrast, a digital signature and identity using cryptography can prove authorship or even ownership, through the use of private keys. In Estonia, where blockhive is based, people are already signing documents and contracts digitally using their own private keys.

As Kusaka notes, “A digital signature with a digital identity can secure personal identification, something which Hanko fails to do. Even a registered seal can only go so far.”

Kusaka acknowledges that there are both cultural and technical hurdles to replacing Hanko in Japan — even at the private, non-registered contract level — in Japan.

On the technical side, he suggests that there is still work to be done to improve the user experience of the xID app. On the cultural side, Kusaka points out the “invisibility” of blockchain technology. Japanese people, he notes, often take great pride in their “craftsmanship culture”, and the elimination of the Hanko risks abandoning a connection to the country’s history.

Hiroaki Nakanishi, head of the Japan Business Federation (Keidanren), says that “Using a seal is nonsense. Everything can be done with a signature or an electronic signature. Using a seal as proof of identity doesn’t fit with the current digital age.”

As the COVID-19 emergency continues to require social distancing, this could be the year in which his argument finally gains enough traction to bring blockchain technology further into mainstream Japanese life.