A few years ago, I would have struggled to point out the tiny Baltic nation of Estonia on a map, and I don’t think I am alone in that. With a population of 1.3 million, Estonia only gained independence — for the second time — from the Soviet Union in 1991, and joined the European Union in 2003.

But its story is a fascinating one, and a complicated relationship with Russia, curiously enough, seems to have helped position Estonia as the world exemplar of digital identity that it is today. With its flagship global e-residency scheme and advanced e-governance practice, it is one of the pioneering nations dominating the highest ranks of the United Nations’ E-Government Development Index (EDGI).

Russian cyberattacks weren’t on my mind two years ago as I traveled to the Estonian Embassy in Madrid to collect my e-resident’s digital identity card. I had applied online a few weeks earlier as I wanted a straightforward way to operate a global limited company (of one) as a Brit living in Spain, to enable me to work with startups anywhere in the world.

Writing about emergent technology and blockchain had led me to discover ‘digital Estonia’ as the perfect virtual home from which to create a distinct trading entity. But I was hardly a trailblazer: as I was later to learn, the country’s love affair with digital identity dates right back to the turn of the millennium.

Digital natives

Taavi Roivas, Prime Minister of Estonia from 2014-2016, told me that “Estonia was basically rebooting the country from 50 years of Soviet occupation, and that needed to be done as effectively as possible. And, of course 20 years ago, it was logical to start digitizing things, rather than relying on paper files or paper documents. So that’s where it initially started.”

Estonia was thus able to choose to avoid the paperwork in which many of the world’s government bureaucracies still drown, and take a secure and transparent digital-first approach to its entire infrastructure — just as parts of Africa bounded ahead of many Western nations in mobile communications and commerce precisely because they weren’t tied to a legacy landline network.

Almost every interaction an Estonian resident (national or e-resident) has with their local or national administration, or indeed other business entities, now takes place via their digital ID and digital signatures.

Ott Vatter, Managing Director of the e-Residency scheme, described the significance of the identity card with its embedded chip, which enables all these interactions:

“We kind of can’t imagine our lives without it. We talk to the government using this card, and we talk to the banks and tax officer, basically everything happens through the card, then if we lose it, we’re kind of helpless, like we’d lost our key to our house.”

In the eyes of Estonian law, a qualified electronic signature is equal to a hand-written signature, stamp or seal; and all authorities and business entities are obliged to accept electronic signatures. In fact, since strange hand-drawn scrawls are considered inherently underhand, to even suggest a written signature is to imply a transaction or decision is suspicious.

The life of an Estonian citizen is digitized from birth with the creation of their health record, which follows them in perpetuity. Their educational records are added as they pass through the eKool (e-school) system, where students, parents and teachers can review every mark or hour of attendance as they follow a decidedly tech-oriented curriculum befitting their future in one of the most digitally focused nations on Earth. A generation of digital-native Estonians is coming of age, and they expect the same innovative user experience from their public sector services as they do from a commercial tech enterprise.

It’s no accident that Estonia has incubated successful startups from Transferwise to Pipedrive to Bolt — Startup Estonia is tracking the progress of more than a thousand of them.

But the favorable business climate and infrastructure mean that not all of these emergent businesses are quite as homegrown as you may imagine: because one important aspect of the digital-first approach to governance has been the global e-residence scheme.

Global citizens of Estonia

Following the launch of the program in December 2014, Edward Lucas, British Senior Editor at the Economist, became the e-resident with ID number 1, to be followed by many others.

Venture capitalist and Bitcoin-community darling Tim Draper was next, followed by more VCs like Guy Kawasaki and Ben Horowitz. Later, premiers of other countries such as Japan’s Shinzo Abe and Germany’s Angela Merkel joined the growing list of Estonian e-residents, along with television host Trevor Noah, former Director General of the European Space Agency Jean-Jacques Dordain, and over 68,000 others. (Oh, and in 2018, me).

Draper has enjoyed practical benefits from being able to open a bank account and trade in the EU, and is inspired by the potential that e-residency and digital identity offers the world:

“The idea that countries could provide government services across borders to anyone. The idea that government could be fairer and more efficient. The idea that governments would have to provide better services for the taxes they charge, or they might be eclipsed by a better government service coming from another geographic location.”

Draper sees a powerful parallel between digital identity and cryptocurrency. “Globalization unites the two concepts. Digital identity allows people to operate wherever they may be. Digital currencies allow people to share in a common value vehicle so that business is frictionless. If countries can identify each of us and compete cross-border for us, we will get better government service. When people use global currency, they have less friction in doing business.”

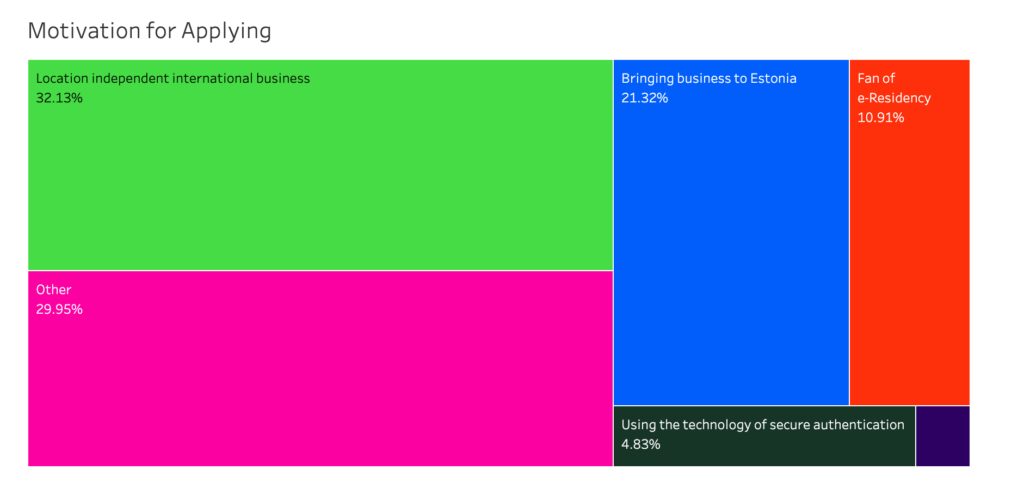

So while many e-residents clearly apply with the purpose of forming a limited company they can easily administer online, others may be motivated by the novelty factor, or the belief in business without borders and the future of work.

In the same way that people are driven to use cryptocurrencies, or even neo-banks or challenger banks instead of established traditional clearing banks, there will always be a segment of early adopters who are willing to trade familiarity for a little risk and a payoff, whether it be lower cost or lower friction.

While not (presently) conferring any right of residence or access to social services within Estonia or the EU, the range of functions and benefits of e-resident status are myriad and growing. The program needed a hardcore base of early innovators to grasp its potential and help get it off the ground; new services and integrations are being built out to support the scheme.

Becoming an E-stonian

Applying to become an e-resident is a straightforward matter of submitting a form to the Estonian border police and paying a fee of €100, then travelling to the local embassy for issuance of the digital keys which make the whole thing work. My appointment in Madrid took about 10 minutes, during which my physical thumbprint was scanned. Since then I have signed every document digitally.

Setting up my limited company as a sole trader didn’t take much longer than that, with the help of one of the many multilingual marketplace providers which have emerged to support e-resident entrepreneurs, and they continue to provide me with a business operations portal and basic accounting services at a price no Spanish service could approach.

As Vatter explained,”E-residency has been an interesting journey that started from the idea of having foreign board members of Estonian companies as digital identity owners, so that they could sign board meetings or documents digitally, so that they wouldn’t have to spend time or money traveling, and they would be able to conduct more business more comfortably.

“From there the idea grew into something much greater, as we quickly understood that there was a greater need for so many more people and target groups. For example there are so many countries in the world which make it very difficult to run a company.”

Securing digital borders

With banking, voting, health records and so much other sensitive data in the system, security has been a critical factor for digital Estonia.

Remember the Russians? Estonia’s history of occupation means that sensitivities inevitably linger. In 2007 a controversial decision to relocate a Soviet-era statue from the center of Tallinn to a discreet corner led to rioting. The Bronze Soldier was originally called “Monument to the Liberators of Tallinn”. For Russian speakers in Estonia it represented the USSR’s victory over Nazism, but for ethnic Estonians the Red Army represented anything but liberation.

As the riots escalated, posts began to appear on Russian-language internet forums supporting armed resistance to local authorities. Within days digital Estonia was hit by major cyberattacks — waves of botnet spam wiped out banks, government offices, communications and more for weeks at a time. EU and NATO technical experts were unable to find concrete evidence of Russian involvement in the cyber-terror incident and Estonian authorities only charged one man, while a Russian official claimed that a rogue aide was responsible. While such attacks are more common today, in 2007 this kind of state-level attack was unprecedented and Estonia had to fight back fast.

It did so in the context of global recognition of the potential of this kind of threat to other nation states in the future, and with the technical support of NATO’s Computer Emergency Response Teams and the EU’s European Network and Information Security Agency. In the end no permanent damage was caused, but as Vatter explained, security infrastructure was strengthened: “Today we host the NATO cyber security Center for Excellence. We have that in Tallinn, Estonia. So, we are considered — together with Israel — one of the top experts in cyber security in the world.”

Decentralization and distribution

I wanted to explore with Vatter exactly how the data is secured in 2020, and he explained that the nerve center of digital Estonia is the X-Road interoperable ecosystem, which is accessed via the EiD (Estonian Identity) Card. There is no data kept on the card itself; it’s a PKI system, whereby users authenticate themselves with PIN one, and seal each deal with PIN two. (For example, I use PIN one to log into my bank and set up a transaction, then PIN two to confirm the transaction. I also use a SmartID mobile app to authenticate the bank login, if I don’t want to physically connect my ID card to a reader.) There’s a public key and a private key on the microchip, but no data, and the public keys enable the trustless interrogation of the various services connected to the X-Road decentralized architecture.

Vatter explains:

“X-Road is like a vast highway, and then smaller roads connect to it. But the smaller roads are connecting roads to different state organizations and databases. Now, on all of these state databases, like the health registry, data is kept safe by blockchain technology, timestamp technology, and you use the certificates that only you have through your pin codes to access this data, — only, of course, if you have the right to access this data.”

“So for example, say I bought a new car. And now I want to re-register the new car from the former owner to my name, so that happens completely online. I need my own digital identity, he needs his own, and he has to start the transaction of owner exchange and I have to sign my key to agree to getting this exchange started. Then the inputs update that data from the registry to show that he is the former owner and now I am the new owner, all using personal ID codes — everything happens online. No written contract, because the platform takes care of everything. It’s super easy and comfortable.”

Vatter goes on to reminisce about the experience of buying a car ten years ago, when it required up to three hours of waiting in a line for documents… And I don’t have the heart to tell him what the horrifically convoluted process looks like in Spain in 2020.

So, while it’s incorrect that Estonia is a ‘blockchain nation’, it was the first nation-state in the world to deploy blockchain technology in production systems (in 2012 with the Succession Registry kept by the Ministry of Justice).

The technology deployed is the KSI® blockchain technology stack by Guardtime, also used by NATO, the U.S. Department of Defense, Boeing, Ericsson, Lockheed-Martin and other global clients.

“There is a misconception that e-residency ‘run on blockchain’, that it’s a blockchain project or something like that”, Vatter explained.

“In Estonia, blockchain is used, or let’s say similar technology to blockchain, a timestamp technology, is used to keep our data safe. So the data of our citizens, the data of our residents, things like healthcare data, is all surrounded by this layer of distributed encryption which is what keeps us safe.”

“So to say, it’s a keyless signature infrastructure, blockchain technology that is developed by one company in Estonia called Guardtime”.

In fact X-Road, like plenty of other applications employing cryptographic hash functions, actually predates blockchain as it relates to cryptocurrencies. Digital Estonia uses the KSI blockchain in combination with a range of other technologies to mathematically secure the personal data on X-Road and its various interlocking systems. While some of the interfaces can seem dated now compared with newcomers — for example, there is no fully mobile digital ID — it works. For over a million people.

Though the country has a healthy relationship with cryptocurrencies overall, I cannot — yet — do business in crypto through my business portal. At least, not as a writer: I would have to re-register as a financial trading company. I wouldn’t be surprised if this changed in future however, and I have managed to account for crypto receipts by immediately cashing in the crypto for fiat and providing a suitable audit trail for that.

I notice that Coinbase in Europe uses the same Estonian bank as I do, and when I asked Roivas about his thoughts on crypto, his only real concerns were around the user experience:

“I don’t understand the concept of cash anymore, because the payments have become so easy I can pay with my not only plastic cards, I can pay with my phone, I can pay with my watch. I can make remote payments. You know, the credit card was invented almost 60 years ago, and this plastic version is also rather crude compared with internet payments. It’s not rocket science anymore, and the same applies to crypto. I think crypto just needs to be more easy to use”.

The present and future of digital Estonia

In the face of a global public health crisis, Estonia has been perfectly positioned for public and business sector continuity. As other administrations grapple with the simple logistics of getting emergency payments to their citizens or carrying out the activities of government, E-Estonia already had the infrastructure in place.

As Roivas explains, “In Estonia, just like in the UK, the main Parliament session is still very ceremonial, but now the virus crisis is something totally new. And even with all our traditions, we decided that in such a crisis, we needed to be able to take our Parliament fully online as well. One hundred percent of the activity, all the committee meetings and all the political party factions, have gone online from the first day of the special situation. Everybody’s using Microsoft Teams for that.”

And as we return to the new normality in due course, he foresees a bright future for digital Estonia and its tech-driven culture:

“Talking about the future work, of course, digital government helps in that if you can take care of all of your official business digitally. There is less need to physically meet up… We know already that video conferencing has already boosted and it will continue to be used at a much higher level than it used to be before the crisis.”

Vatter sees opportunities for Estonia as a model for other governments as they begin to perceive the advantages of digitization. “We were already approached by a few EU institutions. There are about 40 institutions in the EU that function on paper, their whole modus operandum was to sign a document and then push a cart through the next office and then get it signed. So their whole life is basically non-existent anymore. They’re not working at all, and because they can’t work there are no decisions that can be made. For Estonia, it’s definitely an opportunity, and we should use this chance to convince governments and private companies to finally go digital, to use proven digital identity systems like ours for transacting because who knows how long this will last? I think the trend of work will change immensely.”

And as work changes, the concept of identity changes, and the meaning of authentication and payment… Can the concept of digital money and broader adoption of it be far behind?

As Draper concludes in an email:

“Other countries should immediately use digital signatures. It saved Estonia 2% of their GDP. And digital identity reduces the crime rate and increases business activity (better trust, wealthier country). And digital voting brings more people to the polls (and it is more honest than most paper-based or booth-based systems).”

“The rest is obvious: easier to pay for government services, taxes, parking, health care, etc. Estonia has a lead, but other countries are trying to catch up. Malaysia now has a virtual residency program, and last I heard Kazakhstan is implementing a virtual citizenship program. Governments are finally starting to try to compete for citizens on the virtual level.”

Beyond the implications to the value of sovereign currencies at a time of apparently limitless quantitative easing, the proof of concept provided by the Estonian government demonstrates that critical systems can operate entirely digitally, an essential factor for mass adoption of digital currency, and one which makes the traditional boundaries of geography and sovereign nations look increasingly obsolete.

Whatever the future looks like, the nimble nation of Estonia and the global startups it incubates will probably be at the decentralized heart of it.

Irony intended.