The DAO, the first leaderless investment fund which operates on code for reaching consensus in decision-making, is championing for the supremacy of the “immutable, incorruptible” code to be freed from the common fallacies of human behavior such as cognitive bias and irrationality.

While the promise of technocratic governance sounds compelling, it is undermined by the illogical human behavior exhibited by the early instigators and investors which led to the inevitable downfall of The DAO, not just as a software program with an erroneous code, but a collective movement propelled by irrational motives.

After gathering honest feedback from early investors, one thing became clear: the potential pitfall had always been lurking somewhere deep in our consciousness from the beginning. It’s the bandwagon effect, blind optimism and emotional judgement that made us turn a blind eye to the fatal flaws of the organization.

Our collective irrational investing behaviour manifests in a few ways, which we identify further on.

Bandwagon effect trumps rational evaluation

Being a DAO token holder presents a can’t-miss-opportunity to potentially change history, because the fund is built on the wisdom of the crowd, which gives every vote the same weight in decision making.

Needless to say participating in such a scheme brings a feeling of significance to the individuals involved: it promises a nearly heroic act where everyone invested in it has a stake in shaping a futuristic movement that could change the world.

David Strayhorn, a self-proclaimed cyberpunk and Bitcoin enthusiast, compared investing in The DAO to the excitement of the rocket-building experiment in the movie “October Sky”, where a bunch of high school kids tried to change history by taking up rocketry.

The community that supported The DAO - most of them cyberpunks, technocrats and idealists like Strayhorn - band together very closely on the values they hold near and dear to their heart. Such a close-knit community can breed acts of conformity without them being aware of it, such as making a highly risky investment decision without properly and rationally investigating the possible outcome.

Jim Yuan, another early investor in The DAO also admitted that in retrospect, “fear of missing out” compelled him to participate.

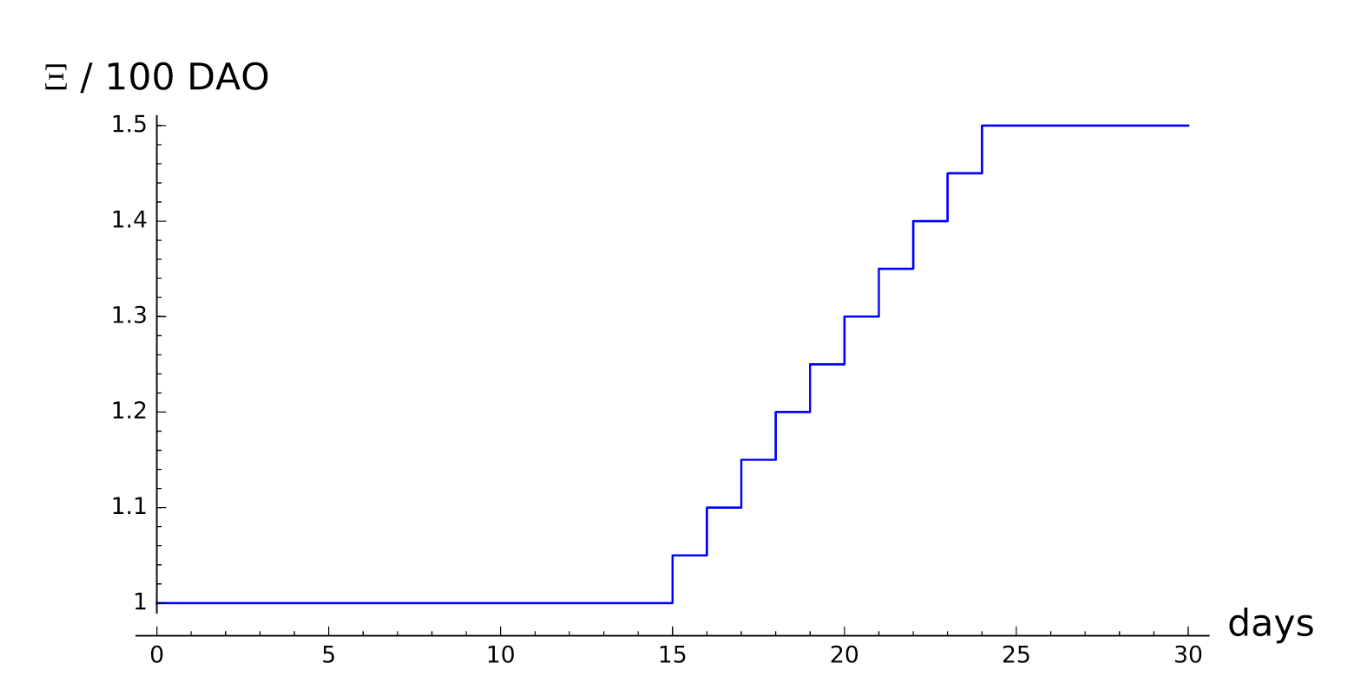

Yuan says that It was worth it to be among the first X number of people who got into The DAO. The FOMO factor was reinforced by The DAO crowdsale, which gradually increased the unit price per every 100 DAO tokens after the first 15 days, making a case to buy in during the first 2 weeks for a better return on investment.

Image provided by Elaine's idle mind.

Stephen DeMeulenaere, another early investor who lost his faith in the platform after the hack, said he “felt pressured to invest in The DAO” when the crowdsale launched, even though he couldn’t get his Blockchain to properly sync up.

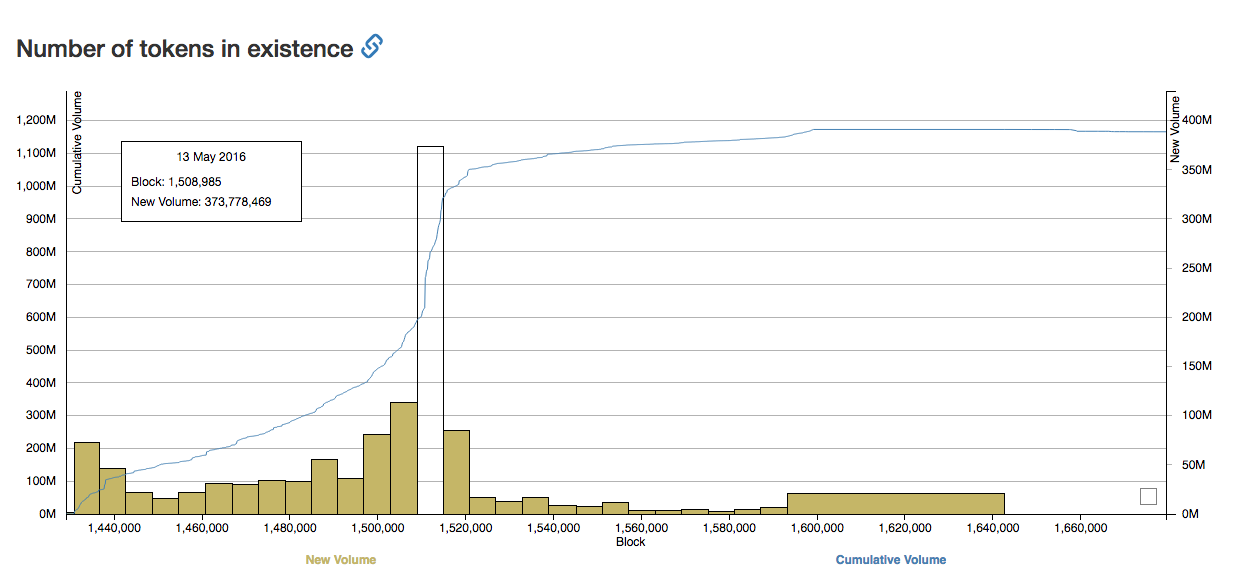

The momentum created by the crowdsale urged early investors to act fast and act early (see the price graph during the campaign period above). As one can see, the fastest growth of the crowdsale happened during the first 15 days before the price increased.

Image provided by DAO Stats.

Confirmation bias led to unexamined confidence

Vitalik Buterin’s voice represents a community of technocratic early adopters who are deeply entrenched in their own beliefs that a machine-enforced process is superior and foolproof. When participants of the movement strongly identify with a charismatic leader such as Vitalik, they tend to overlook contrary voices of criticism and selectively search for evidence that confirms their pre-determined belief instead.

Vitalik’s influence on the crypto community is comparable to that of a spiritual cult leader, as described in the article on Backchannel magazine. The writer described Vitalik as a public persona “to be admired and adored” and that with Ethereum Vitalik “is building a platform that has inspired people he hasn’t even met to completely rearrange their lives and professional priorities.”

With the influence he had already gained from Ethereum, Vitalik’s role as a curator of The DAO gave the project undue credibility. Like many believers in Ethereum’s potential, Strayhorn says he believes “Vitalik is the real deal” which gave him an instant credibility and trust in The DAO without further investigation.

In a well-constructed argument advocating for the virtues of DAOs, Vitalik made the case that DAOs’ ability to supercede whatever incentives are driving the individuals behind the organization and act according to nothing but its “source code” makes it “not even possible for the organization’s ‘mind’ to cheat”.

He argues:

“As society becomes more and more complex, cheating will in many ways become progressively easier and easier to do and harder to police or even understand. Perhaps the true promise of DAOs, if there is any promise at all, is precisely to help with this.”

There were some critical voices warning of the fatal flaws of The DAO, such as Emin Gün Sirer, Cornell University CS Professor.

However, such warnings are drawn out by the overwhelmingly supportive voice from opinion leaders and the media, such as Consensys Media’s campaigns advocating for The DAO. The crowdsale’s impetuous moment and overly self-congratulatory media message was a dangerous combination which prompted the original DAO investors to act too hastily.

Onto DAO 2.0?

Some sober voices, such as Emin Gün Sirer’s, have warned us that success and failure of a DAO/DAC depends not on the technology used, but entirely on how a community interacts with the technology and each other.

Even if The DAO solves the problem of a corrupt gatekeeper with hard-coded rules, it doesn’t solve people problems as those discussed above, including among other potential issues such as a lack of due diligence necessary for making sound investment decisions.

The lessons learned from The DAO collapse is two-fold: for leaders and builders of the platform, it is unrealistic to assume perfect rationality from all the participants as if they are machines running on immutable code. For investors, they need to do their due diligence and actively combat their own biases as all good investors do.