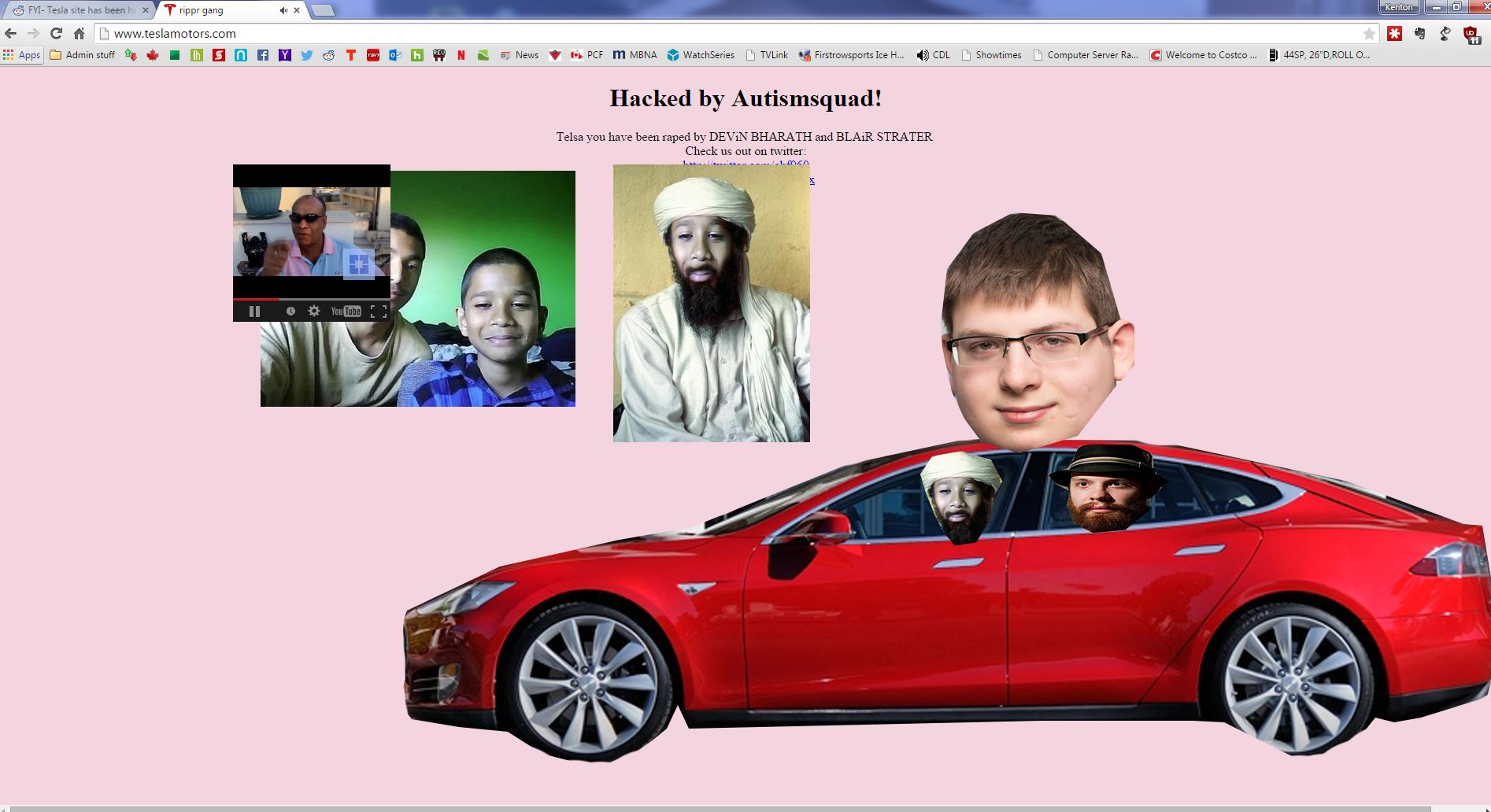

The domain name belonging to Tesla Motors was hijacked this past week, and visitors to the website were treated to a juvenile display of fake photos on the homepage.

The attackers took control of the "teslamotors.com" domain name and used it to not only redirect website traffic to a server they controlled, but to intercept email sent to users on the domain, and even to reset the password to founder Elon Musk's Twitter account.

Controlling a domain name means you have the ability to direct all traffic for that domain including web, email and anything else. People often make a big deal out of a defaced website, but this is typically the least serious, albeit most visible result of a breach. Passwords to all sorts of accounts can be reset, for example, if you control the email accounts for a given domain name.

The attacker(s) apparently used a social engineering attack to route calls to a phone they controlled. Next, they used the invalid Tesla phone number to verify a change they requested to the admin account at the registrar of record, Network Solutions, a Web.com company.

Once they were able to access the registrar account, they chose to change the nameserver entries, pointing all web and email traffic to their own servers.

Not satisfied with defacing the official website and intercepting email, the vandals requested a password reset for the founder's Twitter account, where they offered a free Tesla automobile to anyone who called a posted phone number.

What could have happened instead?

Tesla Motors got lucky. Apparently the attackers were pranksters, which was fortunate for Tesla. Lucky, I say, because they were not malicious actors. They didn’t intend to deface the website, but simply use it to infect viewer's machines with malware.

Lucky also since the attackers were not interested in stealing the domain name. They could have simply transferred it to an overseas registrar account. You might think that getting back a stolen domain name would be simple in a centralized system such as we have, but history suggests otherwise.

Lucky too because the attackers did not engage covertly with Tesla customers. The in-car app communicates with Tesla via an API at "owner-api.teslamotors.com." The attackers could have quietly redirected that traffic to a fake server with a modified API that stole user information, returned fake responses, delivered malicious software to the cars, and who knows what else.

Luckily, these were not sophisticated agents, hired by competitors or organized crime outfits to do some serious troublemaking. This hack had the indicators usually associated with bored college kids not intent on doing real damage to people and companies.

What could be different if they used blockchain-based DNS?

In future, I think it's safe to assume that for the sake of security, companies will opt for blockchain-based DNS. No registrar is needed in these new systems, which is particularly nice given that registrars have abysmal track records for keeping customers' domain names secure. It's hard to talk a decentralized blockchain into doing something, or to trick it into doing favors.

With blockchain-based DNS, there is only the private key, without which no one can make changes, no exceptions. Web and email traffic cannot be redirected without presenting it.

The zone file in a traditional DNS is easy to tamper with because only a password is required. But domain registrants in decentralized systems can easily guard against a private key being stolen, lost or given away by. Keys can be protected both by requiring multiple keys be presented and/or by breaking keys into smaller pieces kept in separate locations.

What could Tesla do in the future? TeslaChain!

Aside from the obvious benefits of being resistant to hijacking and immune from the incompetence of empowered third parties (registrars), using a blockchain could offer many substantial benefits to Tesla in the years to come, beyond secure DNS.

The API by which Tesla cars communicate with the company could be secured by using a blockchain. If Tesla and each automobile would publish their public keys in the official blockchain, there would be no opportunity for man-in-the-middle (MITM) attacks to occur between these parties. The in-car app is currently the only user of Tesla's APIs, but if it were demonstrably secure, the cars could indeed engage in much richer sorts of exchanges with Tesla, as well as authorized repair centers, leasing companies, financing companies, insurance companies and more.

The blockchain is, in fact, a terrific place to store records related to the automobiles, precisely because of its tamper-proof nature. If Tesla were to run their own blockchain, with only approved nodes being able to mine blocks (publish transactions) they could house warranty and purchase information, ownership and leasing data, maintenance history, accident details and much more on-chain — all nicely timestamped and replicated across the network in a fashion that would be both tamper-resistant and convenient.

Adopt the chain, Tesla, and realize the benefits of using this distributed system, as your vehicles increasingly become computer networks with fancy and expensive hardware attached to and controlled by them. MITM attacks on automobiles will likely increase dramatically in the years to come, and blockchain technology could be used to thwart them.

By the way, if someone at Tesla thinks that further elaboration would be useful, feel free to send me a shiny new Tesla in exchange for specific observations and suggestions about the possibilities.