What will a Greek or Spanish exit look like for the European Union and what will be its implications for the global economic picture?

The popular media has all but guaranteed a compromise with Greece that would include a debt restructuring and a promise that the union will stay intact. But despite this guarantee, there is presently a stalemate between Syriza and the rest of the European Union that may preclude a possible deal and increase the chance of a Greek exit (Grexit).

Even if an agreement is reached as promised, it could have a ripple effect on Spain, whose own election is looming in the early fall and the far leftist Spanish party, Podemos, is already ahead in the polls. By all accounts, they are even more radical than Syriza.

Lessons from Other Breakups

In 2012, Anders Aslund, a Swedish economist and a Senior Fellow at the Petertson Institute for Economics wrote a paper in 2012 titled “Why Breakup of the Euro Area Must Be Avoided: Lessons from Other Breakups.”

His work focuses on the economic transition from centrally planned economies to market economies and the consequences of such transitions. In his paper, Aslund uses 3 examples of currency unions in Europe that failed:

- the Habsburg Empire in 1918;

- the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991;

- and the disbanding of Yugoslavia in 1992.

In the analysis, Aslund concludes that "the Economic and Monetary Union must be maintained at almost any cost." This is because the 3 above examples all ended in disaster with spiraling hyperinflation.

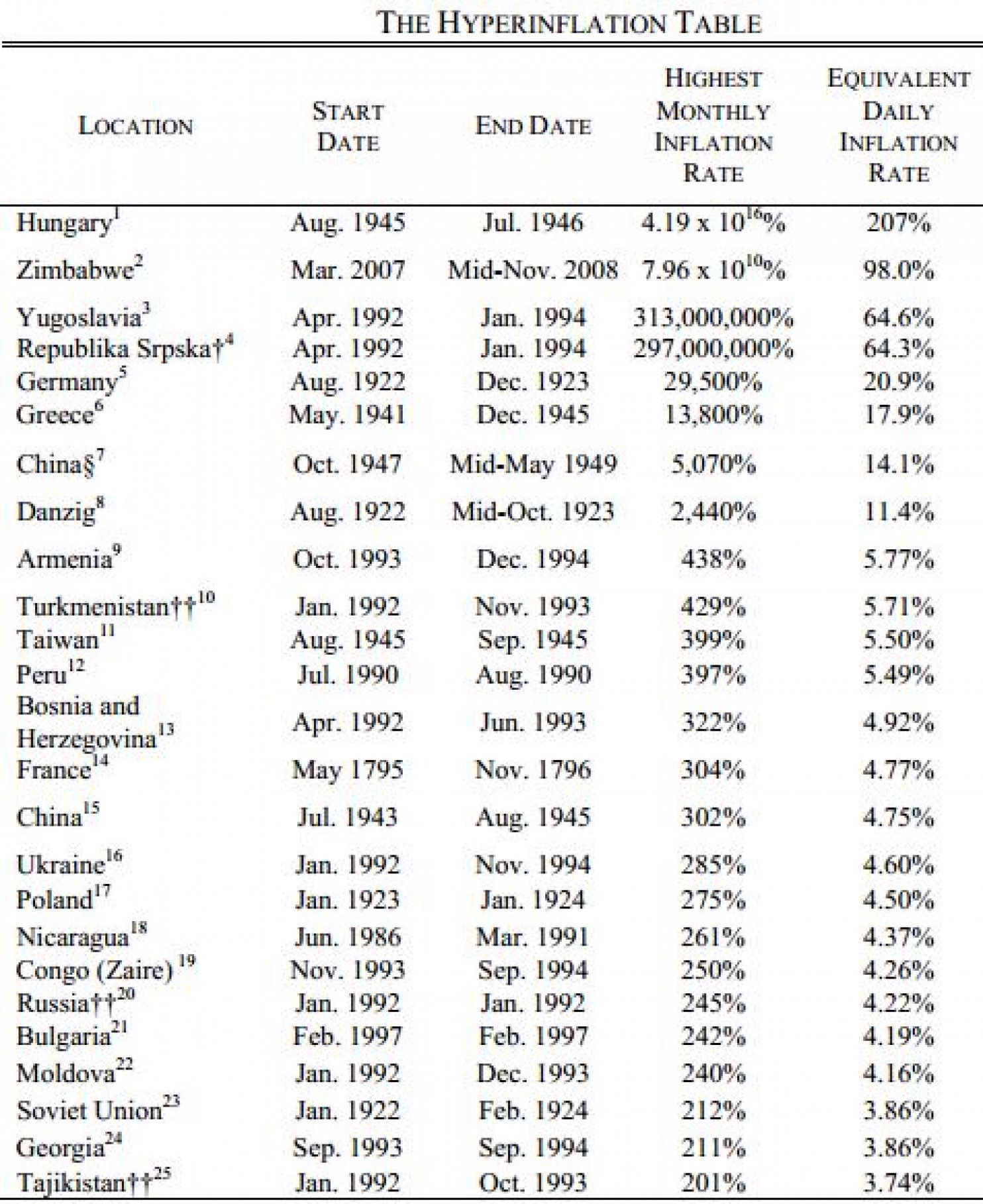

If you look at the table below of the greatest hyperinflationary episodes in history, Hungary (part of the Habsburg Empire) tops the list. In fact all 3 examples make the list, including some of the satellites of the Soviet Union breakup as well as Yugoslavia. Both Austria and Hungary (Habsburg empire) experienced hyperinflation. Across the former Soviet Union, 10 out of 15 republics experienced hyperinflation while the former Yugoslavia underwent hyperinflation TWICE.

What is Hyperinflation?

The standard economic definition of hyperinflation is that it occurs when a country experiences very high and usually accelerating rates of inflation, rapidly eroding the real value of the local currency and causing the population to minimize their holdings of the local money.

The population normally seeks a flight to safety in the form of relatively stable foreign currencies. Under such conditions, the general price level within an economy increases rapidly as the official currency quickly loses real value.

To quantify it, Steve Hanke and Nicholas Krus of the Cato Institute believe it can be defined as any monthly period where the inflation rate rises above 50%. In this scenario, people do not want to hold their money as it is expected to rapidly devalue, which incentivizes spending it on real goods and services as soon possible since exchanging into other more stable currencies is nearly impossible and very expensive.

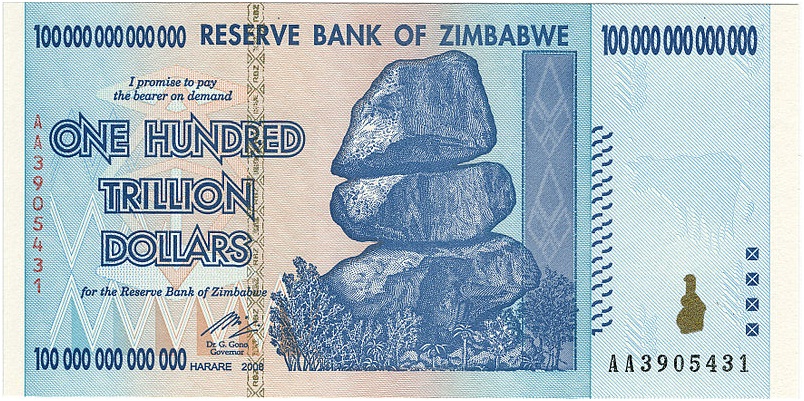

Think of images of Zimbabwe where the stores are empty and people are lined up around the block to buy what comes in. There is a real and justified fear that your money will be worth less in hours, so spend it as soon as you get it.

What are the Causes of Hyperinflation?

While touched upon in the previous paragraph, hyperinflation has a few main causes. Hyperinflation is usually caused by large persistent government deficits financed primarily by money creation. It is generally a two-fold process where there is a supply shock, which leads to giant output falls coinciding with a continuing and rapidly accelerating increase in the money supply that’s not associated with an increase in economic growth. This leads to a shortfall in goods and services. Output falls are associated with very negative economic activity.

The causes of these large output falls were multiple systemic changes, competitive monetary emission leading to hyperinflation, collapse of the payments system, defaults, exclusion from international finance, trade disruption, and wars. Such a combination of disasters is characteristic of the collapse of monetary unions.

According to Haslund:

“In the case of the Hapsburg Empire (Austria and Hungary), war led to hyperinflation. In the cases of the Soviet Empire and Yugoslavia there was major systemic changes. The combined output falls were horrendous, though poorly documented because of the chaos. Officially, the average output fall in the former Soviet Union was 52 percent, and in the Baltics it amounted to 42 percent. According to the World Bank, in 2010, 5 out of 12 post-Soviet countries—Ukraine, Moldova, Georgia, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan—had still not reached their 1990 GDP per capita levels in purchasing power parities. Similarly, out of seven Yugoslav successor states, at least Serbia and Montenegro, and probably Kosovo and Bosnia-Herzegovina, had not exceeded their 1990 GDP per capita levels in purchasing power parities two decades later. Arguably, Austria and Hungary did not recover from their hyperinflations in the early 1920s until the mid-1950s.”

EMU Exit: None or All

Aslund sees these examples as extremely relevant to the situation in the European Union today. The crux is that all 3 monetary unions had a centralized payments system that had built up large imbalances (just like the European Union) and had a tumultuous exit.

Aslund argues that this exit would be very disorderly accompanied with the exiting countries who will then go onto re-establish their own central banks and currencies to compete against the Euro. This competition between currencies within these currency zones is historically responsible for hyperinflationary episodes.

But what makes the EU situation even more complex is the size of it. The bigger the size, the more disorderly it will be due to its increased complexity. “When things fall apart, clearly defined policymaking institutions are vital,” writes Aslund, “but the absence of any legislation about an EMU breakup lies at the heart of the problem in the Euro area. It is bound to make the mess all the greater. Finally, the proven incompetence and slowness of the European policymakers in crisis resolution will complicate matters further.”

Aslund believes a Greek or Spanish exit would not be possible without dire consequences. “Exit from the EMU cannot be selective: It is either none or all,” he writes. “The breakup of a currency zone is far more serious than a devaluation.”

He further explains:

“When a monetary union with huge uncleared balances is broken up, the According to Brad international payments mechanism within the union breaks up, impeding all economic interaction. A new payments mechanism may take years to establish, as was the case in the former Soviet Union. Meanwhile, the collapse may lead to a host of disasters. Almost half the cases of hyperinflation in the world took place in connection with the disorderly collapse of three European currency zones in the last century: the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Yugoslavia, and the Soviet Union. It is easier to establish a monetary union than to break it up.”

Willem Buiter, the chief economist at Citigroup has stated, that he sees an escalation of financial panic with bank runs, big devaluations, proliferation of exits from the EMU, liquidity freeze, defaults, and legal conflicts. Presuming a complete breakup of the euro area, he predicts that “[d]isorderly sovereign defaults and eurozone exit by all five periphery states…would trigger a global depression that would last for years, with GDP likely to fall by more than 10 percent.”

By All Means Necessary

Based on the three examples listed above and the strong similarities between them, an exit of one EU member nation (Greece or another periphery nation) would constitute a shock big enough to realize both Aslund’s and Buiter’s visions (see above) of hyperinflationary chaos throughout the Eurozone and the world at large.

We are seeing calls by some of the greatest minds in Europe to keep the EU together no matter what the cost. It is doubtful that ailing periphery nations will ultimately place the union above their own self interests as this strategy has been increasingly falling out of favor with the general populations in Portugal, Italy, Spain, and Greece, which continue to be worse off than they were pre-EU.

The real problem continues to be the output gap in these nations. Meanwhile their competitiveness has not risen under draconian austerity policies. Austerity doesn’t work, ask Italy and Portugal. Now, it seems that The Union has reached a crossroads where the resolve of these separate interests will be tested and the consequences of these decisions will affect the global economy catastrophically if the EU cannot find a way to resolve this major problem. Even if it stays intact, the current fiat system is broken and an alternative system needs to be put into place accompanied by responsible policy making.

It is a deep conflict of interest to have one central bank rule a currency zone when there are no equal voting rights on the policy instilled by that organization, especially in a time when large imbalances exist inside and outside of that monetary union.

It appears that the EU is yet another casualty of the currency wars and will have to find a way to keep this ill-fated union together for now. Trying to have economic integration before political and social integration has never worked and the Euro experiment could eventually find itself in the annals of hyperinflationary history alongside the Hapsburg Empire and Yugoslavia.

Did you enjoy this article? You may also be interested in reading these ones:

- Deflation vs. Disinflation vs. USD strength

- Currency Wars, Commodities, and Deflation

- The Drum Beat of Deflation is Growing Louder: The Intermarket Picture